Exploring the secretive world of cycling agents

The Tour’s start signals game-on for cycling’s mysterious deal-makers. Chris Marshall-Bell unmasks the role of agents

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

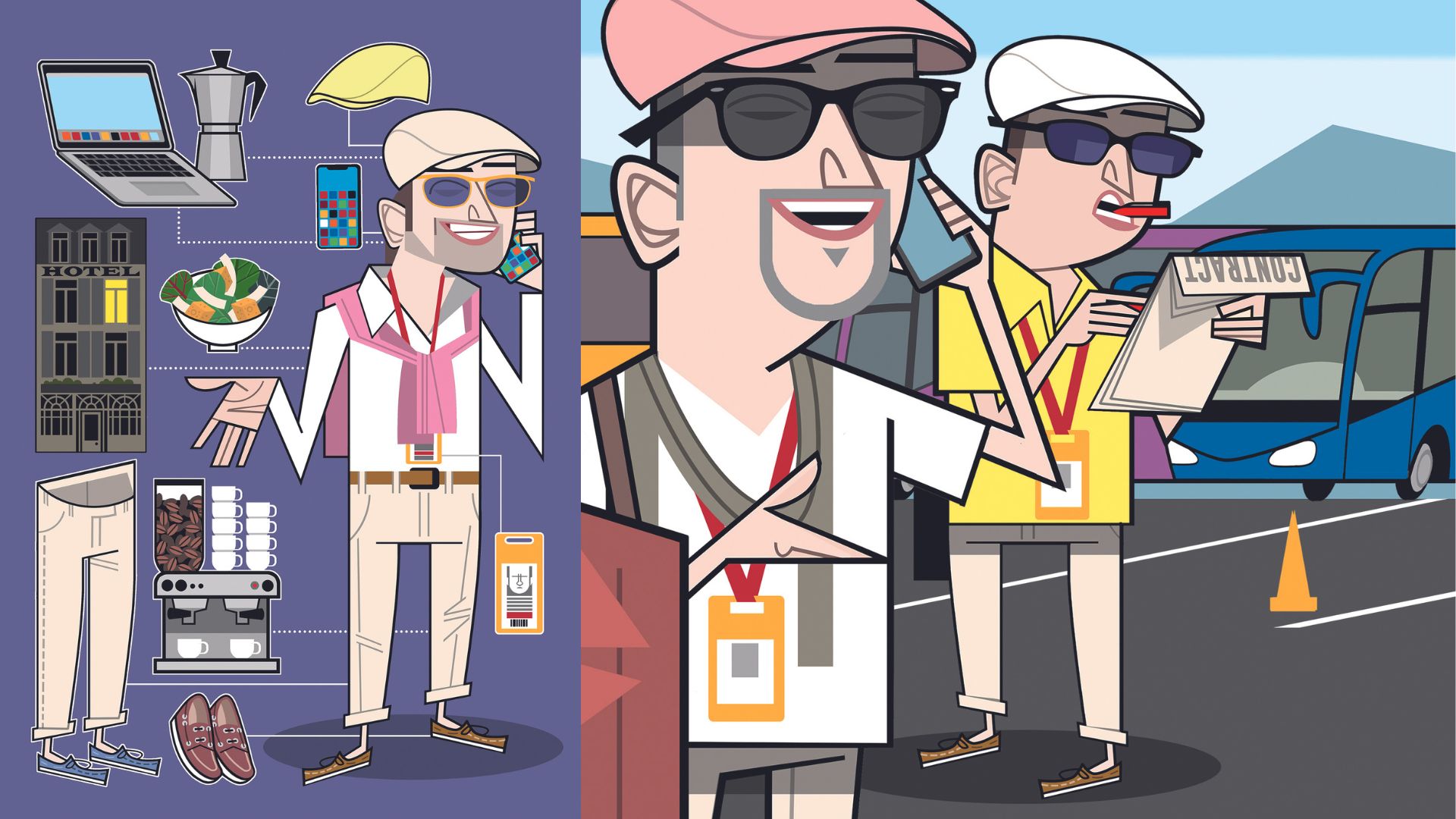

Among the hundreds of people milling around team buses in Florence at the Tour de France's Grand Depart was a small collection of of men unknown to those outside of cycling’s inner circle. They were there to shake hands with the protagonists and engage in high-stakes discussions. Dressed in flat caps, rolled-up chinos and deck shoes – almost an unofficial uniform – they are the agents who represent the world’s best-paid stars.

These influential men move cycling’s chess pieces around the board year on year. And the start of the Tour is a particularly important time for them, because tradition dictates that the race’s two upcoming rest days are their time to do business – two 24- hour periods during which, in quiet hotel bars and tiny cafes, contracts are negotiated and transfers finalised. These days, some deals are done earlier, typically during May’s Giro d’Italia, but agents remain totemic figures in the Tour’s travelling circus. Just who are these powerful, mysterious men and how do they exert such a big influence on the sport while remaining more or less hidden from view?

Open to all

Agents might live very secretive professional lives, but anyone can become one. All you need to do is sign up and pass a UCI riders’ agent exam, mostly testing knowledge of regulations, at a cost of 600 Swiss Francs (£525). There are currently 85 registered agents worldwide. “Anyone could just turn up and pass the exam,” Gary McQuaid, a Brighton-based agent from Altus Sports Management, tells me. “All the reading material is on the UCI’s website and it’s a case of learning that.” Once passed, agents can start working on behalf of riders for two years at a time. However, qualified lawyers, such as Gary’s cousin Andrew McQuaid of Trinity Sports Management, are not required to pass the exam, nor are direct relatives, who can act as an athlete’s manager without taking the test – Remco Evenepoel is managed by his father, Patrick.

Day-to-day life for an agent involves making and receiving phone calls and emails, while flying all over the world with represented riders. “I like to consider myself part of a rider’s performance team,” McQuaid says. “On top of moving them from team to team and liaising with their employers, I help them with relocation, finances, and commercial deals such as shoe sponsorships. It’s much more complex, strategic and planned than simply rocking up at the Tour and negotiating next year’s contract.” The role has evolved over the past decade, he explains: “Traditionally, an agent’s role was centred around post-Tour criterium negotiations. That’s still around, but a core part of our job is talent ID and signing [young] riders who’ll become future stars.”

Currently, McQuaid’s agency has 21 riders on its books – a number typical of most agencies, although SEG, a Dutch agency, has almost 90. “I’m not in the volume business,” McQuaid says. “We’re pretty selective with who we work with: we’ve got a bit of credence on the wall, and we don’t manage riders who want teams; we manage riders that teams want.” That said, McQuaid does informally help lots of junior and U23 riders by “circulating their CVs because they might deserve a break.”

Is there rivalry and bad blood between agents? “There’s an unwritten code that we are mutually respectful towards one another,” McQuaid says. “At the Tour, I’ll have dinner with several agents – we’re in the same bubble and we wouldn’t go after each other’s bike riders.” Curiously, A&J All Sport’s Alex Carera, the agent of Tadej Pogačar, disagrees with McQuaid. “If we are friendly or not, we’re in competition with all other agents,” the Italian says. “With some agents there is a better relationship, but with some others we fight every day. For example, do you think no other agent would want to manage Tadej? It’s a great pleasure and not difficult to work with Tadej because he’s a smart guy, but if I don’t do my job, he’ll go somewhere else.”

It is expected that Pogačar will soon sign a contract extension with UAE-Team Emirates with a projected value of €8m per year. When I ask Carera how big a slice of a rider’s contract finds its way to an agent’s bank account, he becomes tetchy. “Some of your [media] colleagues call me Mr 5%,” he says. “They’ve given me the nickname of Shark and Cowboy. I don’t know why they call me that, but, yes, an agent takes between five and 7% of a rider’s contract.” Other agents have told me that their commission rarely exceeds 10% – Carera’s range is evidently competitive. “For sure it’s a good business – if it wasn’t, I wouldn’t have stayed in the sport for more than 20 years,” he adds.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

It is not mandatory for pros to be represented by an agent. Canadian pro Michael Woods is currently operating without one. “Agents are financially driven and too many of them mislead riders by saying they’re going to manage them but then don’t,” the Israel-Premier Tech rider says. “Some say they’ll help with taxes and residential issues, but more often than not, it’s the rider dealing with it all.” When are agents useful, then? “One quote I heard was that 99% of the time they’re absolutely useless, and the other 1% of the time they’re the most important person in your life,” Woods adds. “And it’s true – on two separate occasions I’ve had my contracts rendered null and void, and agents have helped me navigate the waters far better than I could have on my own.”

Cav has a longstanding sponsorship deal with Oakley

Brand endorsments

Scroll through the Instagram feeds of the sport’s biggest names and you’ll see a clutch of private sponsorship deals: Tom Pidcock and Wout van Aert promoting Red Bull; Mathieu van der Poel and Mark Cavendish sporting Oakley sunglasses; and Tadej Pogačar telling the world about the supposed great taste of Jana water from his native Slovenia.

Such agreements have been commonplace for decades, but according to agent Gary McQuaid, these personal sponsorships are becoming “problematic” from teams’ perspectives. “If a team is paying a bike rider €400,000 a year,” he says, “and the agent is saying he’s got a local bank willing to pay €30k a year for fi ve appearances, the team’s stance is that those appearance dates will get in the way of training. As a result, they’ll not want to approve the sponsorship, as they don’t want additional distraction and noise.”

The assumption that Red Bull’s private athletes earn megabucks from their relationship with the energy drinks giant is also flawed, McQuaid says. “This is pro cycling, not football. These deals will be done with the regional headquarters, not the worldwide operations. No matter the profile or the fame of the bike rider, they’re not Cristiano Ronaldo, and these private sponsorships will be pretty small compared to the salary that their team is paying them.”

Rights of spring

The pinnacle of the sport remains the Tour de France, but no longer is it the headquarters of transfer dealings. “It started about eight years ago but especially in the last five years there’s definitely been a shift towards contracts being signed during or even before the Giro, especially the bigger ones and for the mid-ranked riders,” McQuaid says. “Whereas before, things would be sorted out over coffee in July, initial chats are now had at the Spring Classics, sometimes even sooner.” Why has everything been brought forward several months? “Multiple reasons,” McQuaid says. “It gives teams respect by telling them much earlier in the season that a rider is off to a new team so they can plan ahead, although you do also have to perform a cloak-and-dagger dance. Another shift is longer-term deals: teams want to go big on riders and lock them down rather than giving them a traditional two-year deal. Before, I’d be organising about 10 contracts a season; this year I have only five. And finally, there’s a rush to sign wunderkinds before other teams do.”

Carera uses the example of the youngest rider and the biggest breakout rider in this year’s Giro d’Italia, VF Group-Bardiani CSF- Faizanè’s Giulio Pellizzari. “During the Giro three WorldTour teams called me about Pellizzari, but it was too late – he’d already signed with a team [thought to be Red Bull-Bora- Hansgrohe] for 2025 onwards,” Carera says. “If you wait until the middle of the season and the Tour, you have no chance of signing the best riders.”

This is not to say, though, that the Tour and its two rest days are no longer busy days for agents – the job has evolved in line with the sport’s new conventions. “During the Tour we’re speaking with teams and riders about 2026 – a whole 18 months away. Before, we’d be talking only about the forthcoming season,” Carera says, “and then there is what we’ve always been doing: relationships with the media, small deals like shoe suppliers, and arranging post-Tour crits. It never stops, but if you love your job, you’re always on holiday.”

A freelance sports journalist and podcaster, you'll mostly find Chris's byline attached to news scoops, profile interviews and long reads across a variety of different publications. He has been writing regularly for Cycling Weekly since 2013. In 2024 he released a seven-part podcast documentary, Ghost in the Machine, about motor doping in cycling.

Previously a ski, hiking and cycling guide in the Canadian Rockies and Spanish Pyrenees, he almost certainly holds the record for the most number of interviews conducted from snowy mountains. He lives in Valencia, Spain.