I joined a cycling team, and unwittingly became a doping whistleblower

When Toby Atkins moved to Italy to race his bike, the last thing he expected was to be dropped into the middle of a doping programme. Chris Marshall-Bell hears his story

Toby Atkins sipped his morning coffee outside a large countryside villa overlooking the mountains in Sicily. “It was at the end of a gravel track, completely off-grid, no Wi-Fi, poor phone coverage. If you didn’t know where to go, you’d never find it,” he recalls. It was a fine winter's day in 2015, and having agreed to race for Italian amateur team T-Vb, the Briton had been driven to their training camp eight days earlier in a soigneur’s two door Alfa Romeo. “He turned up an hour late,” says Atkins, “and I had to empty my two suitcases into this tiny sports car, ditch the cases at the airport, and wedge my bike in."

Those eight days of training went well, and now he was taking a well-earned break. “The team were impressed and said they wanted me as a leader for the season.” But during an informal chat with T-Vb’s manager Mattia Vairoli, Atkins was handed some unidentified pills accompanied by a terse instruction: he would have to take them if he wanted to further improve.

As he finished his espresso on the terrace, Atkins was joined outside by Vairoli. “I got the pills out of my pocket and threw them across the table,” says Atkins. “I said, ‘I know what you’re doing and I’m not going to be part of this.’ He stared back at me for what felt like an eternity. You could see the gears in his mind going over and over, pondering how to respond.

“Eventually he grabbed the pills and said, ‘Come with me.’ He pulled me inside, marched me into the bathroom, slammed the door behind us and locked it. What the f**k is going on? It was like I was in a real-world gangster movie.”

The not-so-funny truth for Atkins was that he really had stepped into a criminal underworld. Aged just 20 at the time, he was taking his first major step in his quest to become a professional cyclist, and in doing so he had been thrown head-first into a sophisticated and organised doping ring. And he was the guy about to bring it all crashing down.

Age of innocence

As a child, Atkins didn’t really know much about cycling. “My family is not sporty at all. I was that unhealthy PlayStation kid,” he tells me in late October, a few months after a random internet search alerted me to his story. Born in Nottingham, he moved to New Zealand aged 12. “It’s a sports-centric society, and you make friends by playing sports,” he explains.

So Atkins did everything: rugby, football, climbing, orienteering, swimming, triathlon, cycling. Aged 15, he rode a 110km sportive and finished as the third-best U23. “It was considerably better than I had expected. I fell in love with the speed, the freedom. I got a lot of satisfaction from pushing myself to the limit. I was hooked.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

He continued to progress as a teenager, and in his second year studying management studies at the University of Waikato in Hamilton, he won a stage of the PNP Tour, one of New Zealand’s premier races. He thought: “I can actually do this. I’m not faking it. I know how to race and I’ve got the legs. I had to decide if I wanted to commit to it, if this was a career I wanted to chase. Halfway through my second year of uni, I started putting feelers out for U23 European teams.” He enlisted the help of family friend Tony Purnell, who in 2013 joined British Cycling’s ‘Secret Squirrel Club’; he was responsible for the national governing body’s tech development.

In the autumn of 2014, Atkins signed a contract for the following season with T-Vb, a well-funded amateur team based in northern Italy. “There was science-based performance testing in November, Trek bikes, good equipment, and it seemed like a forward-thinking team. It was exactly what I was looking for. I was really excited.”

January rolled around, and Atkins flew to the southern Italian island for a three-week training camp, before moving to a team house in Veneto. “I was nervous about it all as I had no idea how good I would be against the rest of them, and only a few spoke good English. But as I was coming off a New Zealand summer, I was going pretty well and my numbers were beyond anything I’d expected. I was meant to be in a leadout role, but only one guy was beating me on the climbs. I was in for a positive season.”

Hunting for evidence

But something was amiss. “We were six days into this training block and the day after performance testing I was a broken soul. I woke up the next day and I was absolutely f***ed. Despite riding stronger than everyone else, half of them didn’t seem to fatigue. This day, there was another six hour-plus ride planned, but I knew I needed an easy recovery day. The manager was surprised when I told him, but he was OK with it.”

What happened the next day came as a total shock. “The next morning at breakfast, the manager sat down next to me and asked for a quick chat. He pushed over a load of pills. ‘They’re vitamins,’ he said. ‘They’re important so that you can maintain your body under harsh training loads day after day.’ I wasn’t going to smash a handful of pills into me, but I said OK and put them in my pocket. I went to my bedroom, looked at the pills and thought they looked odd. Every packet of pills had a medicinal code on them, and I typed this code into Google. ORG-DV3. The webpage finally loaded up: testosterone capsules.” During that day’s coffee stop, Atkins continued to investigate on the internet. What he read shook him. “What the f**k have I got myself into? I was in proper s**t. The next day, I called Tony and said I wasn’t sure what I was dealing with. That night he texted me saying it was more serious than we first thought. Because of his position within British Cycling, he had to report it to the UCI. The next day, a UCI lawyer called me and explained how serious it was.”

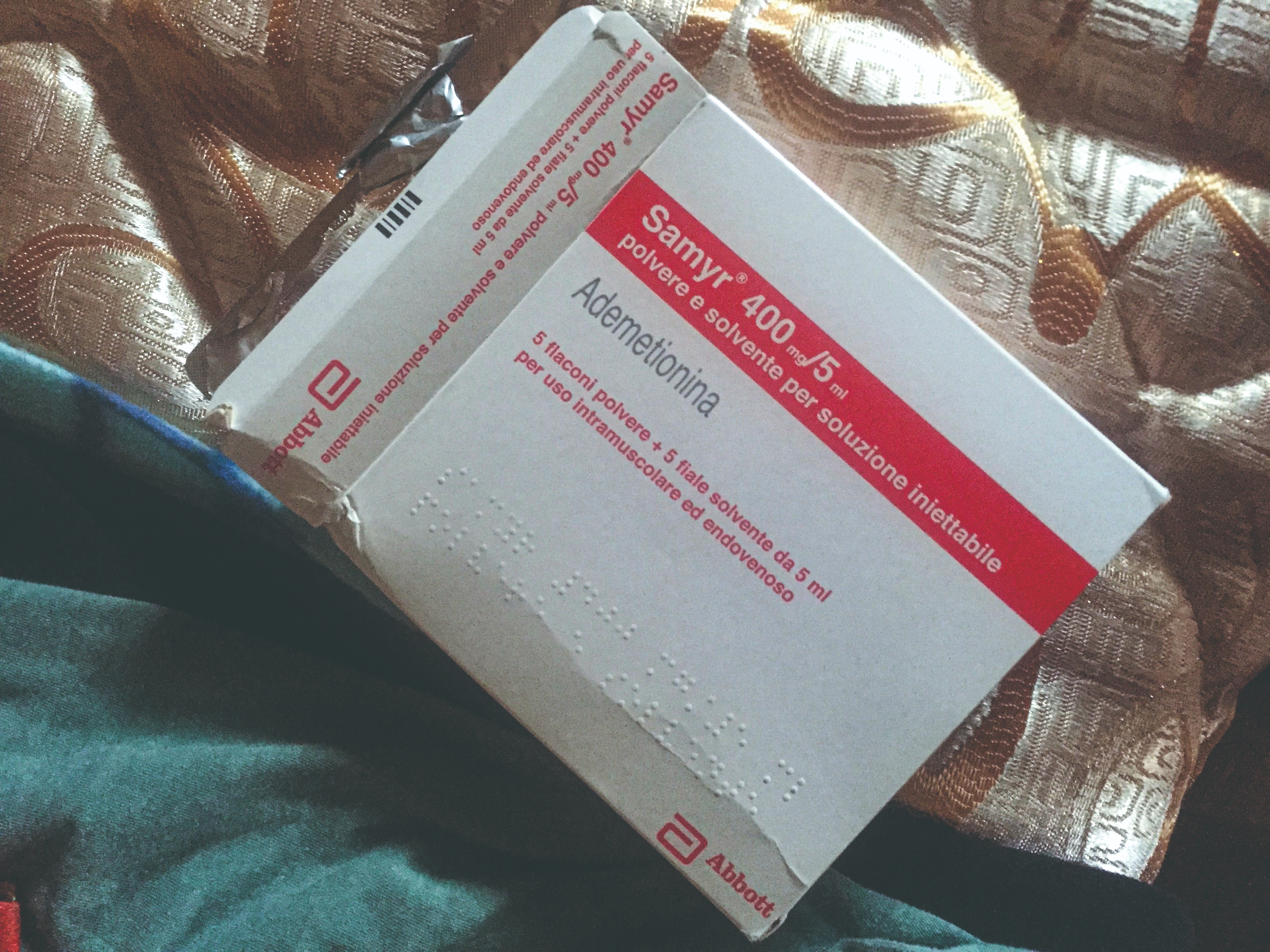

Toby was offered Russian branded testosterone tablets

Unwittingly, Atkins had become a whistleblower on an explosive doping conspiracy. “[The UCI representative] said that the UCI needed proof before they could do anything: photos, phone recordings, something they could use as evidence of malpractice. Because of the danger, though, they couldn’t support me. But I wasn’t walking away, quitting. I was going to come out of this looking good.” He decided to buy himself time to do some fact-finding. “The next day I told the team I had a knee injury and would be staying at home to rest. The entire team left and there was just me in the house. I went looking under people’s beds, through suitcases, wardrobes, cupboards. In all of the rooms I found pills, needles, vials, everything under the sun. It was all Russian branding. It was properly orchestrated, although I still remain confident it wasn’t the entire team cheating. I took photos and videos, walked up the road to get a good signal, phoned the UCI, and sent them what I had. They said they needed to get me out of there, as I was in a potentially dangerous situation.”

Time to quit

Facing down Vairoli in the locked bathroom, having just spelled out that he wouldn’t be taking the pills, Atkins had no way of knowing what would happen next. Eventually, after a tense silence, the team boss spoke. “He got the pills out and threw them down the toilet and flushed it. He started saying, ‘It was just a test! You passed the test!’ He was trying to get out of the situation, but he had no idea that I had seen everything and reported it. He then walked out of the bathroom as if nothing had happened. It was the weirdest thing I’ve ever experienced.”

Therapy helped Atkins look back and process his trauma

Atkins now had to plan his escape. “We went out training, carrying on as if it was no big deal. I told the manager I didn’t feel like it was the right environment for me. He was overly helpful, realising at this point he was going to be in deep trouble. He told me not to tell the riders why I was leaving. At 5am the next day, I was taken to the airport. The UCI phoned me when I landed in the UK. They said: ‘Toby, we’re glad you’re OK’.” The youngster was safe, but his world had crumbled all around him: he had quit university, moved halfway across the world, and now he hated the sport he had adored just days before. “I got back and I went off the rails. I didn’t want anything to do with cycling. Everything I had worked towards for seven years was gone in an instant. I started drinking a lot, going to the pub five nights a week and getting battered – I’d be a complete write-off. I was using drinking to stop thinking whatever I was feeling. My mum was terrified for my wellbeing.”

The spiral of destructive behaviour continued for months. “Almost a year later, I went to a therapist and I got diagnosed with depression. It took me multiple years of therapy until I could accept what happened.” Eventually Atkins got back on his bike and even returned to race in Italy for five months. He continued racing at an elite level in the UK and New Zealand until 2021.

Police raid

A few months after escaping from Sicily in 2015, Atkins went back to New Zealand. Months later, in the middle of the night a Swiss number flashed up on his phone. It was the UCI’s lawyer. “They hadn’t contacted me since I left Italy, and I had assumed they hadn’t done anything. But the lawyer informed me that, as doping is a criminal offence in Italy, they had informed the police and so weren’t allowed to contact me.

Three things I learnt

1) Just because someone is a good person, it doesn’t mean they won’t cheat. It’s not a direct correlation that only bad people dope.

2) The pressure of elite sport is immense, and nothing is certain as an athlete. Therapy helped me hugely and I would advocate it for all athletes who are struggling.

3) In a race at the end of 2015 [riding for a different team], some former T-Vb team-mates recognised me in the gruppetto and they tried to make me crash. The whole peloton turned on them. It made me realise just how many people are united in clean sport and doing things properly.

“He told me that a team of 70 carabinieri – Italian gendarmerie – had raided the manager’s and riders’ houses, arrested lots of people, targeted riders with doping tests at races, and that the manager was to be put in jail for several years. It was a weight off my shoulders.”

The kingpin Vairoli would eventually avoid a prison sentence, but was banned from the sport for six years. “For a long time I was bitter about it all, and I don’t forgive him, but I don’t need closure anymore. He’s paid the price.” At the end of 2015, Atkins started working for the UCI on its #IRideClean whistleblowing initiative, and later for the International Testing Agency’s (ITA) education anti-doping programme. At the time of speaking to Cycling Weekly, he was living just outside Nottingham, and running a vehicle repair business. “After what I went through, I'm keen on making sure that no other 20-year-old goes through the same s**t – stuck on a remote mountain, their entire life suddenly turned upside down. I know I did the right thing.”

Atkins the anti-doping ambassador

By talking to vulnerable young athletes, Atkins hopes to spare them his ordeal

Following his ordeal, Toby Atkins came to the opinion that “the whistleblowing system is terrible. The theory goes that speaking out is going to ruin a career and you’d be a hated figure. I wanted to change that.”

He took up a role with the UCI’s #IRideClean programme in late 2015, and since 2019 has worked for the International Testing Agency (ITA) as an education ambassador and expert. He travels around the world giving talks, seminars and delivering anti-doping education to sportspeople from a variety of sports, as well providing an athlete’s perspective to anti-doping officers.

“A big part of what I do is speaking with juniors and U23 age groups, the points where people are most mouldable and influenced. I tell them that it’s OK to have thought about cheating, because most elite athletes have. In a vulnerable moment, such as going from best junior to fifth-best U23 and at risk of losing funding, it’s normal to consider what else can be done to get a better result.

“I teach them about recognising when these moments might pop up to prevent them from happening further down the line. I also inform them that speaking out, like I did, is no longer frowned upon, and there are people at the end of a phone line at the ITA and WADA [World AntiDoping Agency] who care about them as a person and will make sure that, first and foremost, they are safe and protected.

“When I speak with athletes, it reaffirms my belief that I am making a difference in what I do.”

This feature originally appeared in Cycling Weekly magazine. Subscribe now and never miss an issue.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

A freelance sports journalist and podcaster, you'll mostly find Chris's byline attached to news scoops, profile interviews and long reads across a variety of different publications. He has been writing regularly for Cycling Weekly since 2013. In 2024 he released a seven-part podcast documentary, Ghost in the Machine, about motor doping in cycling.

Previously a ski, hiking and cycling guide in the Canadian Rockies and Spanish Pyrenees, he almost certainly holds the record for the most number of interviews conducted from snowy mountains. He lives in Valencia, Spain.

-

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much more

Gear up for your best summer of riding – Balfe's Bikes has up to 54% off Bontrager shoes, helmets, lights and much moreSupported It's not just Bontrager, Balfe's has a huge selection of discounted kit from the best cycling brands including Trek, Specialized, Giant and Castelli all with big reductions

By Paul Brett

-

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-Liège

7-Eleven returns to the peloton for one day only at Liège-Bastogne-LiègeUno-X Mobility to rebrand as 7-Eleven for Sunday's Monument to pay tribute to iconic American team from the 1980s

By Tom Thewlis