Are young riders turning pro too fast, too soon?

Cycling’s rising stars are turning pro at ever younger ages – thrilling for the sport, but what about for the riders themselves? Chris Marshall-Bell investigates

Cormac Nisbet was one of Britain’s most promising juniors in 2023. Signing for Soudal Quick-Step’s development team in 2024, the pathway to the top had opened up for him. “The team is unbelievable and everything was set up for me to excel at Quick-Step,” Nisbet says. But just eight months into his U23 career, the young Londoner realised that the dream he’d chased since the age of nine – to become a professional cyclist – no longer appealed to him. “There were two main reasons: one, the danger of the sport has massively increased. We’re racing alongside people who we know might go on to lose their life in a bike race later in the season,” he says, “and two, there’s a lack of mental stimulation when you’re a pro cyclist.” The fire within him had burned out.

Nisbet, who turned 20 in January this year, wasn’t the only one hanging up his wheels early. His French team-mate and contemporary Gabriel Berg also quit the sport, citing being “trapped in a routine – cycling, cycling, cycling all the time. Outside of cycling, I saw no one. I had no social life.” Nisbet echoes this sentiment. “It’s a simple life: you ride your bike, travel to a race, race your bike, eat chicken, pasta or rice in average hotels around Europe, and it’s quite robotic,” he goes on. “And because of the inflexibility of it all – you can get called up to a race 10 days before – you can’t get a part-time job or study for a degree on the side, as you don’t know where you’re going to be in two weeks’ time.”

Though the average age of the peloton hasn’t changed very much this century – this season’s youngest WorldTour team, Bahrain-Victorious, has an average age of 25.8, while the oldest, Lidl-Trek, has an average age of 28.6 – since 2019, riders under the age of 23 are scoring more points than ever before. In an analysis for Pro Cycling Stats, Mark van der Linden crunched the numbers and found that, of the generation born in 1980, the first 20 pro race winners had an average age of 23.4 years. Skip forward to the generation born in 2002 and the first 20 winners had an average age of just 20.6 years. Van der Linden also found that only four to eight riders under the age of 20 signed for WorldTour teams each year from 2008 to 2017, whereas that number leapt to 15-19 each year from 2022 to 2024. The WorldTour’s youngest male rider in 2025, Decathlon AG2R’s Paul Seixas, only turned 18 at the end of September.

Pogačar is a poster boy for aspiring cycling prodigies

Turning pro younger doesn’t guarantee success, of course; not all teenage tearaways ape the trajectory of Remco Evenepoel or Tadej Pogačar. On the contrary, some are deciding that the lifestyle of a professional athlete and all that it entails – the fixation on data, daily weigh-ins, little or no indulgence, the pressure and expectation, reduced socialising, 250 days away from home a year – is not for them. There are riches on offer and dreams to be fulfilled, but in committing to a life of cycling, a young athlete also faces a number of hazards and potential pitfalls.

Pushy agents

For decades, football, tennis, rugby and countless other sports have had well-funded youth set-ups and academies producing a conveyor belt of talent. Teenage athletes live like professionals alongside their school studies with the aim of achieving their sporting dreams. Cycling, a sport where convention dictated that most didn’t turn pro until they were 23, was finally, albeit slowly, signing up to the youth playbook in the late 2010s, but it took the emergence of Pogačar and Evenepoel, two generational talents, to really accelerate the revolution. All of a sudden, riders in their early-20s were the champions of the sport. Since then, signing ever younger riders has become the norm, and most WorldTour teams have launched development and even junior operations, each eager to jump the queue for the next superstar.

“It’s all about making sure you don’t miss out on the next big hope – what’s driving the change is the fear of missing out,” says John Herety, the manager of Great Britain’s U23 team. The hunt for emerging young riders has led to accusations that teams and agents are participating in a form of exploitation to ensure that they land the signature of the burgeoning superstars. “It might not be the right word to use, but for me it’s a form of grooming, especially the predatory instincts of some agents when targeting parents of the riders,” Herety adds.

Pickering left no stone unturned in his quest to turn pro

Of course, some would argue that the change represents progress in the nurturing of talent. Standards have markedly stepped up across youth, junior and U23 categories, largely helped by the universal adoption of smarter training tools and greater accessibility of information around training and nutrition. Very few riders are winging it anymore. Making it to the top requires absolute commitment, with no fallback plan. “I put all my eggs in one basket,” said Finlay Pickering, a 22-year-old Brit riding for Bahrain-Victorious. “If you’ve got a get-out-of-jail card, you’re not willing to put everything on the line.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

This approach yields sporting success, but it has drawbacks. On top of the upheaval of moving away from home for the first time, with its accompanying administrative and emotional burdens, comes the pressure to perform. “I think nowadays the pursuit of success is a lot more unforgiving for younger riders,” Ineos Grenadiers’ veteran of the peloton Bob Jungels points out. “There should be a time to have beers and a time to weigh your rice. To have a long-lasting career, you have to find your own balance. I think teams sometimes take less care in building a rider up… you already see it with younger riders deciding it’s not for them anymore – you didn’t really have this in the past.”

Seeing the bigger picture

When Nisbet reflects on his history in the sport, he’s not bitter or regretful. “Without cycling, I’d be a different and weaker person than I am today,” he says. “I could sit here and say it’s a hard struggle with no social interaction whatsoever but that wouldn’t be true; cycling as a whole has given me a lot.” And as he peruses his options, including enrolling in an economics degree and competing in triathlon races, bikes will remain a big part of his life. It was the day-to-day rigour of full-time cycling that didn’t chime with him. “My second year as a junior in 2023 was incredibly enjoyable – it was the best year of my life from a sporting perspective, and I think that was partly because I was also sitting my A-levels in the first half of the year, and it gave me a life outside of cycling. But as an U23 rider, I was of the belief that if I was going to do this, I had to fully commit to it, have no distractions, and give it full beans.”

Xandres Vervloesem, the winner of the prestigious U23 race Ronde de l’Isard in 2020, ended his career aged 22 after two years racing in the WorldTour for Lotto Soudal. “I lived like a priest because I thought racing would make me happy, but I was certainly not happy,” the Belgian said at the time. The now 24-year-old recalls how as a teenager at school, he was “racing and living my dream while my friends went to parties”. Initially, he believed it was they, not him, missing out. “At the time I had the belief that I was somehow better than them – I was chasing my dream and they were wasting their time. But now I realise it’s just as important to have some fun. Day and night, my mind was thinking about cycling. The bike should have been part of my life, not all my life.”

Safety was another factor in Vervloesem’s decision to quit racing

Vervloesem was losing his zest, and it was noticed by those closest to him. “My dad was seeing that my happiness levels were going down. When I had crashes or illness, I was questioning if this was really what I wanted.” The problem, he believes, was the pressure – mostly self-inflicted – to make progress as quickly as possible. “I needed to let the team see I was capable of results,” he says. “When you become a pro young – and I turned pro too early – you have to progress fast, but you can’t force your body to recover faster.” He believes the workload was too much for his developing body. “In the end, I didn’t really feel healthy. If I was sick, I’d always be back on the bike a day or two too early because my mentality was that I couldn’t wait. I believed too much in the training plans on the computer.” Safety was playing on his mind too. “When you cycle from a young age, when it’s the only thing you want in life, you almost say it’s normal if I die like that because that’s the risk,” he says. “When I stopped cycling, I saw that how I went downhill was really crazy. What the f**k was I doing?”

Are poorer youngsters priced out?

One consequence of the professionalisation of cycling at the youth and junior levels has been the increase in cost. CW has heard the story of one family spending £50,000 a year on equipment and travel-related costs for their two school-age children. Understandably, this has led to concerns that many families and kids are being priced out of the sport. Michael Tarling, the father of Ineos Grenadiers’s Josh and Israel Premier Tech Academy’s Finlay, recently tweeted that “we begged, borrowed, remortgaged multiple times and loaded credit cards to give our lads the support they needed. Always second- and third-hand equipment until last year junior when they were lucky enough to get sponsors. We’re financially screwed as a result.” Tim Ferguson, the father of Cat Ferguson and manager of the Shibden Hopetech Apex junior team, told us: “The cheapest bike is a few grand, and if your kid races road, cross and track, and therefore winter and summer, the yearly cost can quite easily get to £15-20k.” The problem is being tackled head-on in Canada, where Cycling Canada has just announced a ban on TT bikes for under-17s at the national championships. It is hoped this will “ensure consistency, fairness, accessibility, increase participation and talent ID.”

Pressure cooker

Despite the experiences of Nisbet, Vervloesem and others, the professionalisation of U23 development set-ups has mostly been heralded as progress, at least in terms of racing education. “They’ve not been around long enough to know if it’s definitely working, but I do think switching riders between WorldTour and development teams, like Visma and DSM [now Picnic PostNL] do, is pretty good,” says Herety. “You’re not overloading riders early on, you’re teaching them the basics of racing, and they can learn slowly.”

But the rush to get onto one of these feeder teams has created problems further down the food chain. “You have junior riders feeling that if they don’t have a pro team lined up, they’re in trouble,” says Jamie Barlow, an Irish agent who manages Josh Tarling and Cat Ferguson, among others. “And you do hear of some kids of that age doing 25-hour training weeks. It might get them their first contract, but you won’t see them in the sport for too long afterwards, as they’ll burn out. There’s a balance between helping riders to develop, but not trying to have them hit their potential at 16 or 17.” There are also individual differences to take into account, Barlow points out. “People develop at different ages and different rates,” he says, alluding to the fact junior success is often determined by who hits puberty first.

Barlow, who admits that the success of young riders he manages has helped to drive this trend, would like the UCI to make one season of U23 racing mandatory for all riders. “We need more layers between the juniors and WorldTour, especially on the women’s side where there isn’t an U23 category,” he says. “I’ve had some male riders skip U23 and it’s a case-by-case basis, but my message to riders is always the same: work hard, have fun on the bike, and enjoy each step along the way. There are some great U23 races that you can’t ride later in your career.”

Another influential voice, Romain Bardet, twice podium finisher in the Tour de France, would like all young riders to study alongside their cycling, not only to give them an escape route if cycling doesn’t work out, but to allow them to mix with people outside the sport. Barlow agrees: “The reality is a lot of riders will have to work after they stop cycling, and it would be fantastic if they could pick up some formal education along the way. I’d be a fan of that and would support it.”

Fun-first approach

Cycling’s youth revolution in the first half of this decade has improved performance levels across the board, but the way of life doesn’t suit everyone. What would Vervloesem – nowadays a team leader in the maintenance of water pipes at the Port of Antwerp – say to his 16-year old self? “It’s better to take your time than trying to force progression. Cycling, like all industries, is hard, but don’t lose yourself in the little details. If one day you don’t want to go riding, don’t. Go for a run or to the gym, or spend time with friends, and the next day you’ll want to cycle.”

As for Nisbet, he remains grateful for the experiences cycling gave him. “My dream was to be a successful WorldTour rider,” he says, “but I came to the conclusion it wasn’t for me once I reached the level I did. It was a tough decision to make, but one door closes and five more open. I have no regrets and am more excited about my future than I was about my cycling career.” Would he warn budding riders against pursuing a pro cycling dream? “My advice is, don’t be afraid to stand up for yourself if the lifestyle isn’t something that you enjoy. Relax, enjoy it, and you’ll naturally discover the career path you want to go down.”

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

A freelance sports journalist and podcaster, you'll mostly find Chris's byline attached to news scoops, profile interviews and long reads across a variety of different publications. He has been writing regularly for Cycling Weekly since 2013. In 2024 he released a seven-part podcast documentary, Ghost in the Machine, about motor doping in cycling.

Previously a ski, hiking and cycling guide in the Canadian Rockies and Spanish Pyrenees, he almost certainly holds the record for the most number of interviews conducted from snowy mountains. He lives in Valencia, Spain.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

-

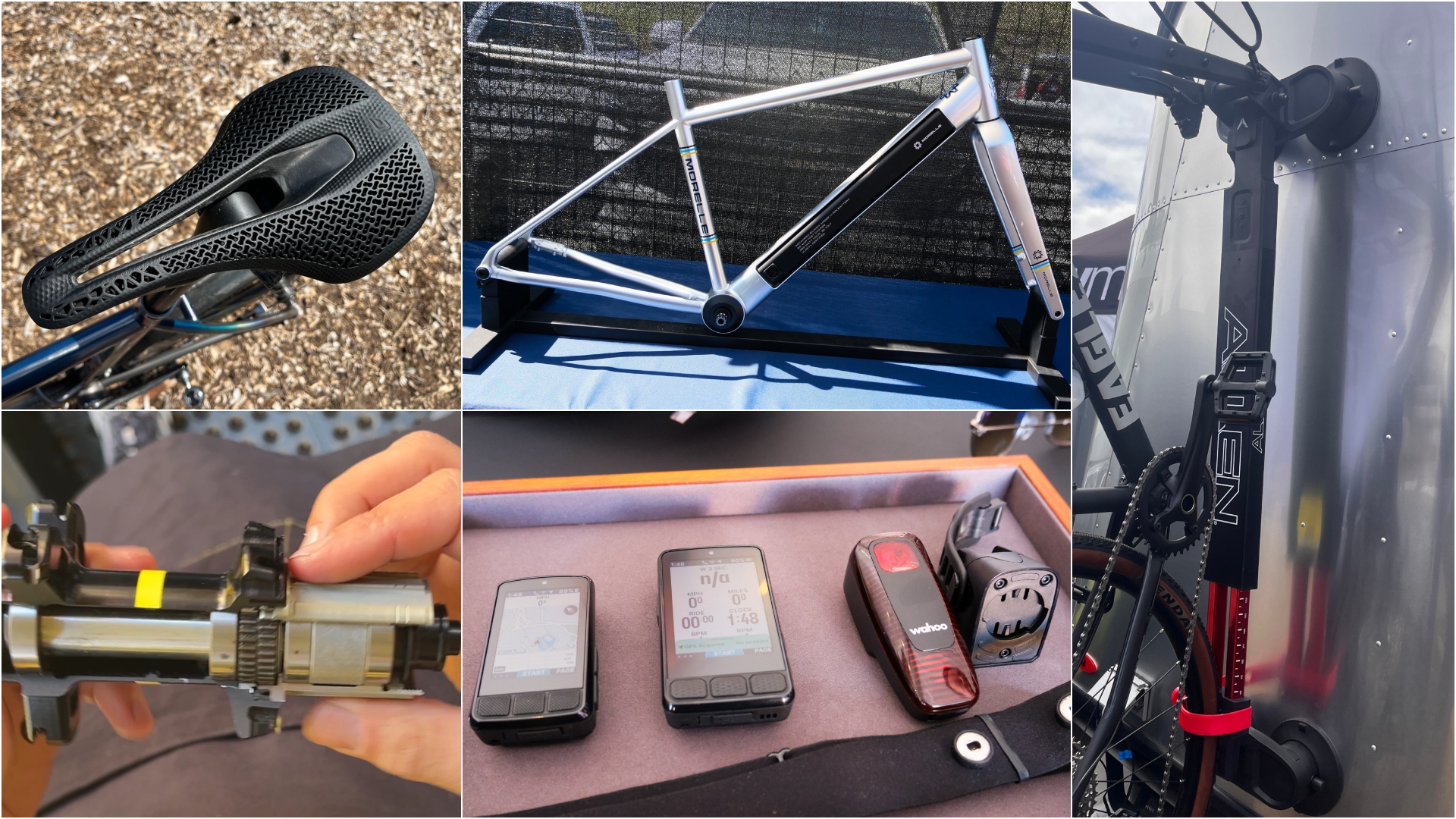

A bike rack with an app? Wahoo’s latest, and a hub silencer – Sea Otter Classic tech highlights, Part 2

A bike rack with an app? Wahoo’s latest, and a hub silencer – Sea Otter Classic tech highlights, Part 2A few standout pieces of gear from North America's biggest bike gathering

By Anne-Marije Rook

-

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incident

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incidentCycling's authorities must do everything within their power to prevent spectators from assaulting riders

By Tom Thewlis