How Roglič, Evenepoel and Vingegaard recovered from Itzulia horror crash to line up for the 2024 Tour de France

Three Tour De France favourites were left broken by a mass crash at April’s Itzulia Basque Country. Chris Marshall-Bell finds out how they fast-tracked their recovery

It was the crash that had the cycling world holding its breath: Jonas Vingegaard on the floor, motionless; Remco Evenepoel gingerly holding his shoulder as he picked himself up; Primož Roglič cautiously stumbling to his feet and into his team’s car; Jay Vine with spinal injuries; and Belgian Steff Cras believing “I would have been dead if I’d fallen 20cm further away and hit the concrete block”. In an instant, one sweeping downhill right-hand curve at April’s Itzulia Basque Country threatened the seasons of so many riders, and also threw the much-hyped four-way showdown between the sport’s best GC riders at this summer’s Tour de France into serious peril.

The next day it was reported that Vingegaard had suffered a punctured lung among other injuries, Evenepoel was nursing a fractured collarbone and shoulder blade, and a mummified Roglič sported dozens of plasters and patches. It looked as if an unobstructed path had opened up for Tadej Pogačar to win his third maillot jaune. But now, with the Tour now in full swing, the prognosis has thankfully improved.

Pogačar remains favourite for the Tour after his Giro d’Italia domination, the Slovenian moved into yellow on stage two with a blistering attack on the Côte de San Luca. However, ahead of stage four, Evenepoel and Vingegaard sit third and fourth on GC, at the same time as Pogačar, with Richard Carapaz (EF Education-EasyPost) wearing yellow. Roglič lost time on the second stage, currently 17th, but with just 21 seconds separating him from the lead.

Both Roglič and Evenepoel managed to get some racing into their legs ahead of the Tour start, the former winning two stages and the GC at the Critérium du Dauphiné and the latter winning the same race’s time trial. Reigning Tour champion Vingegaard didn't race between Itzulia and the start of the Tour, but early stages suggest he's on form, finishing with Pogačar after stage two's attack.

The four-way battle for supremacy is well and truly on – a remarkable turnaround in circumstances given the proximity of the Tour to the crash that threatened to upend everything. How have they bounced back so quickly – and indeed, how do elite cyclists fast-track recovery from injuries that seem to us mere mortals to be season-ending, if not worse? First, though, are the aforementioned big four sufficiently healed to duke it out in the titanic tussle we'll see in the coming weeks?

April’s Itzulia Basque Country crash sent Tour plans into a tailspin

Superhuman, super access

Aside from the relative youth of professional sportspeople, there is one main difference that separates the recovery times of elite athletes from those of amateurs: access. While you or I might have to spend half a day in A&E waiting for a scan, and several more days awaiting surgery, cyclists at the top of the game are in and out of operation theatres in the time it would take us to book an initial appointment.

“A normal person would wait three weeks for an MRI scan, but athletes can get one done immediately,” says Dan Lorang, Red-Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe’s head of performance. “The same goes for operations – they have immediate access to experts. It means we can react really fast to a situation, enabling the athlete to come back faster.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The advancement in indoor training set-ups has also accelerated recovery times – especially when compared to comebacks of previous decades. “After surgery, a rider can quickly go on the home trainer and do training sessions that are really effective,” Lorang says. “Every ride on the indoor trainer can really boost performance.”

But hours spent on Zwift and priority admittance to surgeons, specialists and physios doesn’t solve all ailments. “If a rider has 10 days off the bike, it takes on average 20 days for them to come back to the same level as before the injury,” adds Lorang. What that means in the case of Vingegaard, who had four weeks off, is that he needed an estimated additional eight weeks of training to recoup the form he had at the Basque Country – just enough time to take him up to the Tour’s start on Saturday.

Rediscovering pre-crash condition is made easier by being blessed with beneficial genes and being used to regularly squeezing everything out of the proverbial lemon. “There are two reasons why these guys recover so quickly: nature and nurture,” says Vingegaard’s coach Tim Heemskerk. “The best guys respond to whatever is thrown at them very quickly: race stress, altitude and heat training; they’re world-class athletes. I also think there’s a connection with recovering between stages in a Grand Tour, and it’s possibly a genetic component that makes them recover fast.

“With Jonas especially, I’ve seen after previous illnesses he has been able to recover so fast,” Heemskerk continues. “I’m not saying it’s superhuman, but I’ve never seen it before. At the altitude camp I heard some riders joking, saying: ‘It’s not fair, this guy improves so fast’.”

A rider and their entourage still have to exercise patience, however; bones don’t magically heal overnight, nor do wounds and cuts. “A coach should always stay on the safe side,” Heemskerk says.

The physio angle

Koen Pelgrim, Remco Evenepoel’s coach at Soudal-Quick Step, abides by the same caution. “You have to make sure that the rider doesn’t do anything that would prolong the recovery process, such as training too early on the road,” he says. “While the body is still healing, it uses extra energy and sleep is affected. A rider may experience discomfort so you can’t train them as if they were 100% healthy. Nor should they be forced into a different bike position, as they might overcompensate and create new issues. It’s all about working to the limits.”

When Evenepoel suffered a fractured pelvis in the 2020 Il Lombardia, the young Belgian sought help from Lieven Maesschalck, a physio who has been fixing big-name cyclists and footballers for the past three decades. What sets the pros from the amateurs apart, Maesschalck says, is that “they can withstand a lot of pain, and have more awareness of their body and condition than regular people, and their muscle memory is also better.” Recovery has to be active rather than sedentary, all the while respecting the injury and the impact of the trauma. “You need to let the athlete’s pain and comfort guide them,” says Maesschalck. “If they can’t do normal training loads, let’s work on their lower back, their abdominals, and their leg muscles. I see and hear of athletes who are overtreated by physios [with too many exercises]. Instead they should be prioritising a smaller range of exercises with the biggest impacts.”

Getting the rider back on the bike as soon as possible is always the guiding target. “It depends on the injury, but the moment the rider can start cycling, they should do it,” Maesschalck says. “They might not be able to do much resistance and power work, but can they do two hours of cadence work? The athlete needs to be efficient, and in the rehab phase, less is more.”

Riders and teams want race organisers to take safety more seriously

Making the Tour safer

Ensuring that a bike race passes off without a major incident is a task that requires the work and support of hundreds of race officials, marshals, police and security personnel. The challenge is particularly pronounced in the Tour de France. “There are 200 different types of road furniture every day for 21 stages,” says Markus Lærum of Safe Cycling, an organisation set up in 2016 to improve race safety. “That means we have a few thousand obstacles over the three weeks we have to protect or warn about. It’s a big challenge.”

One of Safe Cycling’s initiatives has been to replace marshals with electronic systems that alert riders to an upcoming obstacle or a sharp turn. “A lot of marshals don’t feel safe standing in the middle of the road with the peloton passing them by at 60kph,” Lærum explains. “The systems we’ve developed remove the need for a marshal in some cases, and the feedback we’ve received from riders is very positive and they want more.”

It is only one year since the tragic death of Gino Mäder at the Tour de Suisse, and in the aftermath of the Swiss’s passing various ideas were proposed on how to improve the safety of mountain descending. “We looked into and tried to push safety nets – like those used in ski racing – but it would require a lot of manpower on a descent with 25 hairpins, so logistically it would be a nightmare,” Lærum says. “We’re now working on a visual warning system to give riders an indication of the sharpness of a turn: is it 180° or 90° change? The system will also tell them how many seconds they’ve got until the turn.”

Vingegaard’s defence

What most hamstrung Vingegaard’s recovery was being stuck in the Bilbao hospital where he was treated for 12 days – having a punctured lung meant he was not allowed to fly. “Every week injured counts against the athlete, causing detraining,” his coach Heemskerk acknowledged. “He lost significant fitness, but the important thing is how he regains it,” he said, ahead of the race start.

Vingegaard’s initial recovery phase was centred on physio and yoga “to try to limit the losses” before a gradual return to the bike ensued; he first rode outside after four weeks. “You have to train smarter; instead of riding three hours straight, do a one-hour ride pre-breakfast, then two hours in the afternoon. Research supports this,” Heemskerk explains.

In late May, Vingegaard decamped to the French ski resort of Tignes for an altitude camp on an individual programme before joining in team training three weeks out from the Tour. “Jonas has always responded well to the training, and he has the highest training compliance I’ve ever worked with,” Heemskerk continues. “We know what does and doesn’t work for him.”

Grischa Niermann, Visma’s lead sports director, tried to downplay Vingegaard’s chances of success at the Tour. Heemskerk has been a lot more positive about the two-time winner’s prospects. “If I wasn’t convinced this was the winning plan for him, I wouldn’t be doing it,” he said.

Evenepoel struggled for form at the Dauphiné

The challengers

Vingegaard’s former team-mate and now rival, Roglič, was the least hurt of the trio in April’s Spanish pile-up, suffering abrasions and a sore knee, but the Slovenian did require a period of rest. What impressed his new employers at Red-Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe was his dedication to rehabilitation. “It’s rare to have an athlete so interested in what they’re doing, but Primož was asking a lot of questions,” says Bora’s head coach Lorang. “His challenging pushed everyone to the next level. It was a real champion’s attitude.”

The fruits of this were evident at the Dauphiné, where Roglič scored back-to-back stage victories and won the race for the second time in three years. “The racing speaks for itself,” Lorang says. “His coach Marc Lamberts and I have checked the data and we can see his training results are better than before. That cannot tell us if Primož can win the Tour, but we know his numbers are an improvement on last year.”

Evenepoel, meanwhile, admitted during the Dauphiné that “the shape is just not there” and that “it’s clear that there’s still some work to do.” Dressed in the rainbow bands as TT world champion, the Belgian did win the race’s 34km test against the clock, but struggled in the high mountains, finishing seventh on GC. Evenepoel pleaded for patience, as did his coach Pelgrim. “Remco suffered a loss of shape because he went three weeks without training,” Pelgrim says, estimating that he would need double that time, i.e. six weeks, to regain pre-injury fitness. “In Belgium we say shape comes by foot and goes by horse – you lose it much faster than you gain it.” With three stages of the Tour now complete, the 24-year-old already wears the white best young rider jersey, and is not far off yellow.

Evenepoel, like Roglič, retreated to Spain’s Sierra Nevada for most of May. “If you don’t go to altitude, it’s not like you’ll miss five or 10%, but you can definitely subtract a few percent,” Pelgrim says. “In the first week of the altitude camp, we did a test and could see... a really big setback in his condition. But we saw it come back gradually”, he said, adding ahead of the race start that he was confident Evenepoel would be able to “close the gaps.”

Roglič’s team put his recovery down to his “champion’s attitude”

The showdown?

A year ago, it was the other one of the big four who was in a race against time to make it to the Tour. Pogačar was fighting back from a fractured wrist sustained at Liège-Bastogne-Liège to be ready for a tit-for-tat tussle with Vingegaard, which he managed for the first two weeks. The young Slovenian, though eventually well beaten by his nemesis, demonstrated that it is possible for the crème de la crème to bounce back and keep a firm grip on goals set at the season’s onset.

“We often see riders come back from injury a lot stronger because they have focused on every detail so much in the recovery process,” says Lorang. “They’ve done core work, stability training, strengthened their back, and they’re more robust than before the injury.”

Whereas it might take a full-time working amateur six months to regain peak form following a broken collarbone or similar injury that requires several weeks off the bike, for the pros who have to be fit for their livelihood, are surrounded by expert support teams, and who a huge financial and personal incentive to get back to winning ways, it’s an entirely different story, as physio Maesschalck concludes: “An athlete’s starting point is really crucial, but I’d estimate that for a variety of reasons an elite athlete recovers about 20% quicker than a dedicated amateur.” The four-way showdown is heating up already.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

A freelance sports journalist and podcaster, you'll mostly find Chris's byline attached to news scoops, profile interviews and long reads across a variety of different publications. He has been writing regularly for Cycling Weekly since 2013. In 2024 he released a seven-part podcast documentary, Ghost in the Machine, about motor doping in cycling.

Previously a ski, hiking and cycling guide in the Canadian Rockies and Spanish Pyrenees, he almost certainly holds the record for the most number of interviews conducted from snowy mountains. He lives in Valencia, Spain.

-

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incident

Cycling's riders need more protection from mindless 'fans' at races to avoid another Mathieu van der Poel Paris-Roubaix bottle incidentCycling's authorities must do everything within their power to prevent spectators from assaulting riders

By Tom Thewlis Published

-

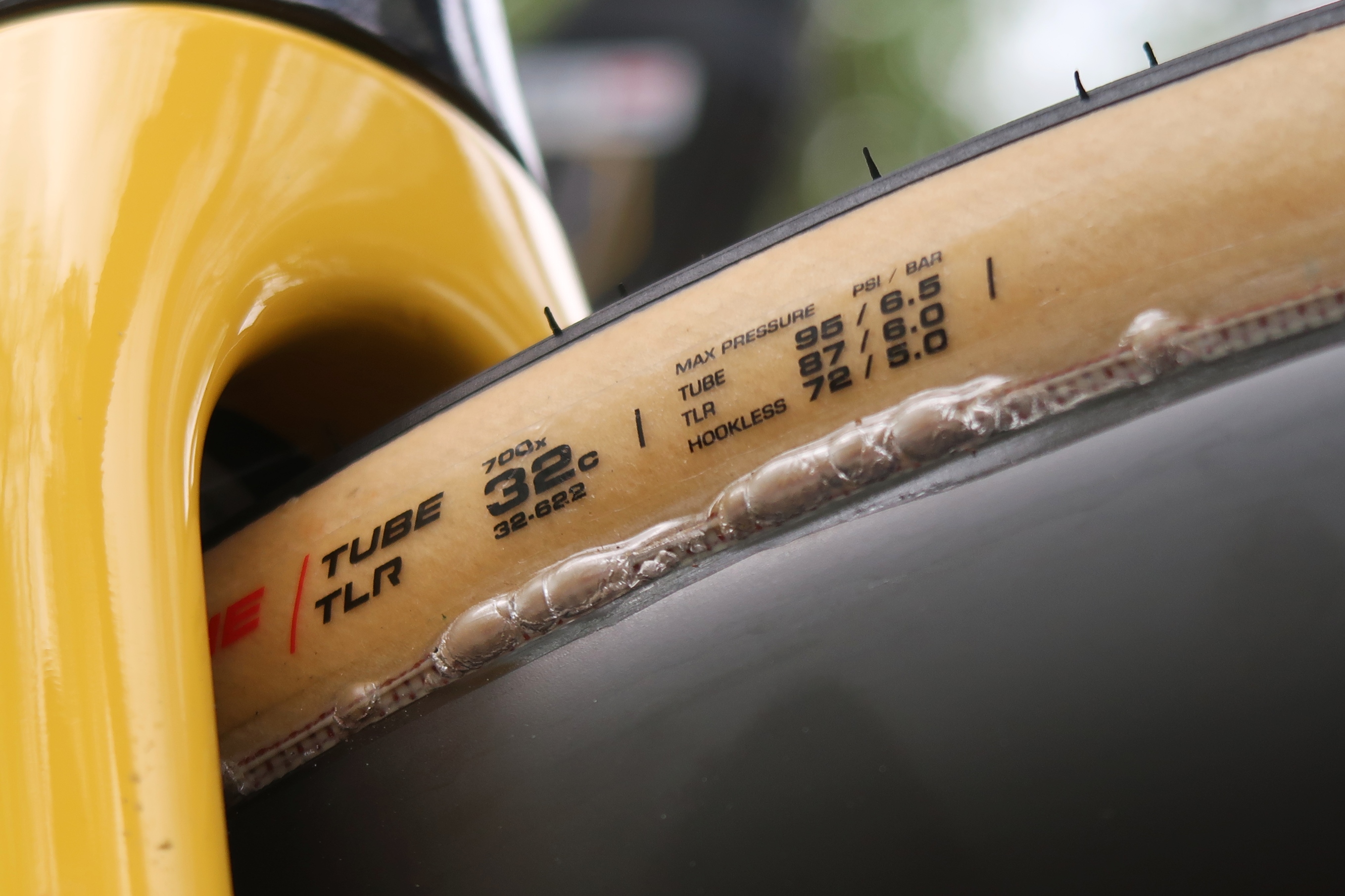

Why Paris-Roubaix 2025 is proof that road bike tyres still have a long way to go

Why Paris-Roubaix 2025 is proof that road bike tyres still have a long way to goParis-Roubaix bike tech could have wide implications for the many - here's why

By Joe Baker Published