Altitude Tent and Everest Summit Hypoxic Generator review

What if we told you that you could get fitter and faster, just through sleeping in your own home? Well using an altitude tent has the potential to do just that. Photos by Daniel Gould

Has the potential to increase performance but results are not guaranteed. Requires some trial and error and is expensive. For most of us, bigger gains can be made by losing a few kilograms

-

+

Can make you fitter

-

-

Can disrupt sleep and relationships

-

-

Results are not guaranteed

-

-

Expensive

You can trust Cycling Weekly.

In order to establish what the performance benefit of an altitude tent might be, Cycling Weekly got hold of a unit from the Altitude Centre.

What is it?

By sleeping in a tent at a simulated high altitude, you reduce the amount of oxygen you are able to breathe in, which forces the body to increase its red blood cell count. Then, when you train back at sea level, you are able to compete more effectively because a greater amount of oxygen is now being delivered to your muscles than before.

>>> Bike Fitting. Which approach is best?

Not everyone has the luxury of training at altitude, so many people, cyclists in particular, hire altitude tents or hypoxic chambers which they will sleep in to get the same effect. Some cyclists have been known to train in them, with some pitching them up over their desk at work.

I hired an altitude tent and slept in it for a month. We all want to be faster and are looking for ways to become faster and fitter. Altitude training can do that, so I decided to try sleeping in an altitude tent to see if an amateur club cyclist, such as myself, could benefit and see a physiological improvement. I was also keen to establish how easy it is to use and live with. Would it disrupt my sleep? Would my girlfriend mind?

>>> The three Rs of recovery

What does it consist of?

Firstly, there is a tent. Our test model is designed to fit over a queen sized bed, with your mattress inside, although other sizes are available. Some tents are large enough that you can comfortably set up an exercise bike or treadmill inside.

The next crucial piece is the hypoxic generator. This is connected to the tent via a tube, and it is this unit which regulates the atmosphere inside the tent.

The tent simulates the atmospheric oxygen concentration at 2,700 metres above sea level — roughly the height of the Stelvio Pass.

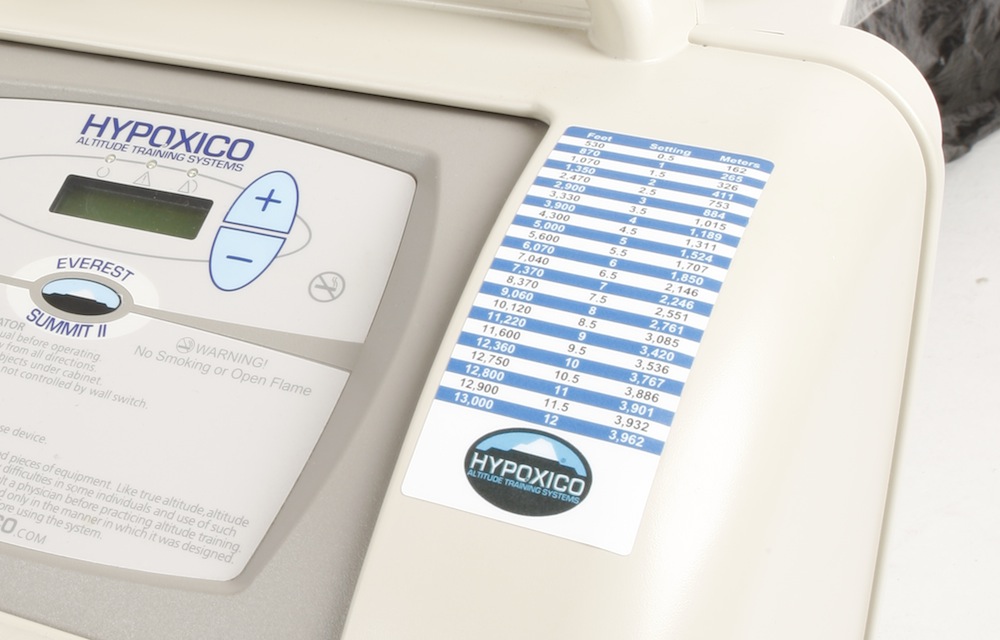

You can use the control to set the altitude you want and it ranges from 0m to 3,962m, which is roughly from sea level to the height of the Eiger in Switzerland.

The other bits of kit are an air filter which fits over the end of the tube and an Oximeter. The filter cleans the air of pollution, pollen and microbes, whilst the Oximeter is used to monitor your heart rate and oxygen saturation levels.

>>> Ketones, the controversial new energy drink

In healthy individuals at sea level, blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) is typically 98-100%. Whilst at 2350m our saturation is likely to drop to around 87-92%. Our heart rate is likely to be higher too.

The guidelines for using the tent suggest you record your blood oxygen saturation and resting heart rate every morning.

How much does it cost?

In the world of elite sport, marginal gains and Olympic gold medals, the price of renting or hiring an altitude tent almost becomes insignificant to professional athletes. But to the club athlete looking to boost their performance in a Grand Fondo or race, the price may be more restrictive.

The system we have on test can be rented from the Altitude Centre for £450 a month or purchased outright for around £4,000. That is a serious amount of money for most of us.

How does an altitude tent make you fitter?

In 2012 Sir Bradley Wiggins spent considerable periods of time living at altitude on Mount Teide, Tenerife. This training proved very successful, with Wiggins going on to win the Tour de France, Olympic gold and a whole host of other stage races.

The idea is that you sleep in the tent at simulated high altitude and continue training at or around sea level. The tent simulates altitude by reducing the oxygen content of the air you breathe.

At sea level air contains 21% oxygen, whilst at 3000m there is effectively 14% oxygen. The composition of the air remains the same at altitude, what differs is the partial pressure, meaning the molecules are further apart (i.e. the air is thinner).

Dr Mark Cole, a lecturer in integrative physiology at the University of Nottingham School of Life Sciences informed us that "live high train low makes sense from a physiological perspective, because from the limited studies that have been done, it seems to offer the biggest effect. It enables you to maintain high intensity training loads, that you wouldn’t be able to do at lower oxygen."

With regards to how to body responds, Dr Cole told us "the kidneys sense that there is less oxygen available and that kicks off a whole series of cellular events in the kidney which results in cells in your bone marrow being released into the blood stream, which then promotes growth of red blood cells. You may get a measurable response within 10 days to two weeks."

How did we test this?

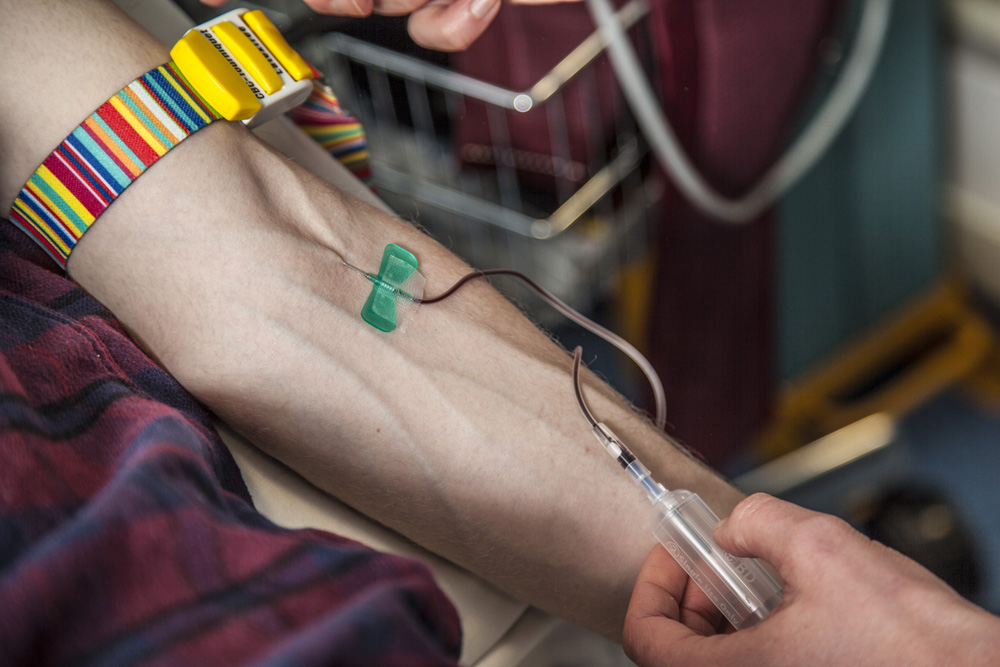

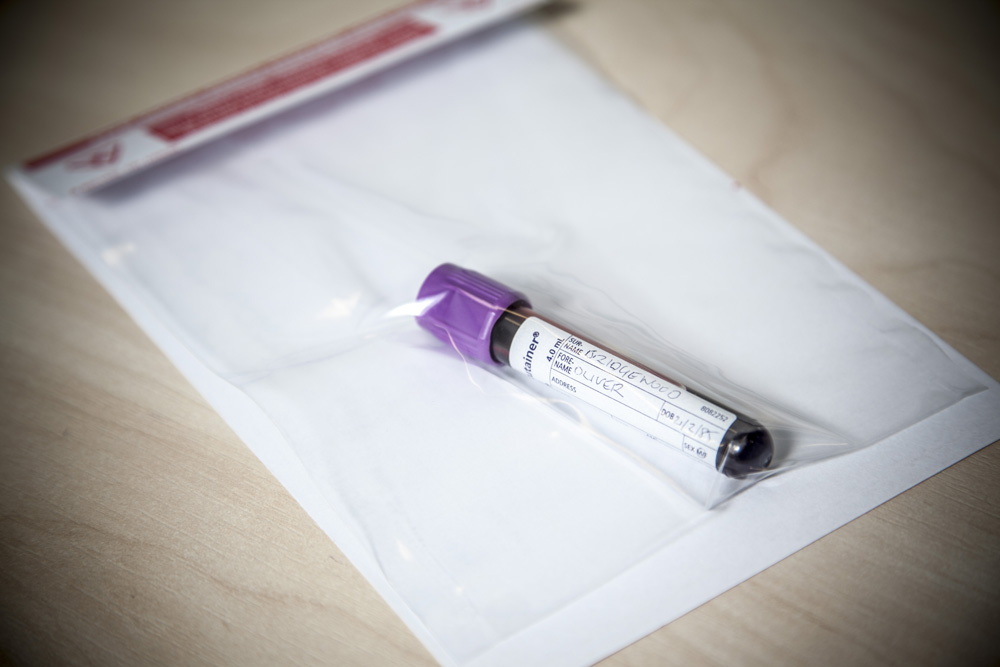

In order to see if this tent will give us any improvement we needed to do some tests before and after sleeping in the tent. Cycling Weekly spoke to leading experts to establish the sorts of things we should look at. Dr Max Testa, Chief Medical Officer of the BMC Racing Team told us "you can do tests before and after to see the effects of altitude, you can do heamatocrit, but a haemoglobin test is most important."

Dr Cole informed us, "haematocrit and haemoglobin are the primary indicators of exercise capacity because they have been shown to be some of the limiting factors, in terms of supplying oxygen to muscle.

"Haematocrit gives you a measure of how many red blood cells you have in a set volume of blood. A ballpark figure for humans is 43% in 1mL of blood, but it can vary considerably. Heamoglobin level is intrinsically tied to how many red blood cells you have, because the haemoglobin is contained within red blood cells and is the part which actually carries the oxygen, so it can be offloaded at the cells."

Our Experiment

- A baseline haematocrit test (volume of red blood cells in blood).

- A baseline haemoglobin test (protein molecule in red blood cells that carries oxygen to body tissue and returns carbon dioxide back to the lungs).

- A baseline 20 min FTP (functional threshold power) test

- A baseline ramp test at sea level and at altitude.

I slept in the tent for a month then repeated the above tests post tent.

As a disclaimer, it is worth noting that this experiment is by no means definitive and not the most scientific, considering we only have a sample size of one.

While different protocols for using altitude tents exist, I couldn't test everything in the time available. Factoring this in, I decided to follow the protocol that the Altitude Centre advises. This involved sleeping in the tent for one month for typically 8-9 hours a night, and not training in it.

Results and discussion

Before I get on to the numbers, I should say that the tent wasn’t the easiest piece of equipment to get along with.

I’m a good sleeper, but I found the tent hot and dry and my sleep quality was affected. Sleep plays a huge role in recovery after cycling, so this was potentially a big issue.

I did however focus on trying to get plenty of sleep, probably about 1.5 hours more a night than normal.

This required the discipline of not watching Newsnight, procrastinating on the internet or getting lured in by the start of Predator at 10pm on BBC1 (we've all been there).

I should also point out that the tent did create a hypoxic environment and I measured my blood oxygen saturation every morning using the oximeter. My Sp02 was 85-89% when in the tent and when not in the tent my blood oxygen was 99-100%.

| Haematocrit | 0.487 L/L | 0.483 L/L |

| Haemoglobin | 162 g/L | 164 g/L |

| 20 min power test (Watts) | 304 W | 337 W |

| My Weight | 68 Kg | 67 Kg |

-

The blood test results suggest there was no change in my haematocrit or haemoglobin levels, as the slight differences lie within the realms of experimental error.

However, I did feel in great shape after sleeping in the tent and my 20 min power was significantly higher, at just over five watts per kilogram.

To add further weight to this, I took part in three criteriums after sleeping in the tent and placed second, fifth and third.

Although no physiological change was observed in my blood values, it may not necessarily mean there was no improvement. “Plasma volume [the fluid red blood cells are contained in] can increase with training, resulting in a lower haematocrit,’ says Dr. Mark Cole, who oversaw the testing.

“This may be working against any increase in haematocrit resulting from hypoxia, resulting in a neutral blood result.”

When I performed my second ramp test in the altitude chamber, I was able to reach the same result at 700m higher than before. This could have been down to physical adaptations, improved fitness, a placebo, or combination of these.

Is it worth it?

It’s hard to tell, some individuals appear to benefit more than others. Dr Cole explains that "the response to altitude between individuals varies a great deal — with the limited amount of properly conducted research available, some people show a very strong response, others show modest or no improvement in performance."

Dr Testa pointed out that "there is no one size fits all; some people don’t have a big response, they are insensitive". Whereas "other people are quick responders. Some recreational guys tell me that they have spent five days at altitude and they come back feeling that everything is much easier."

From my experience I would suggest you factor in the quality of sleep you will get in the tent, as it can be affected. Convincing a partner to use the tent too is not going to be easy, and the high cost can’t be ignored.

Although my FTP increased significantly it is important to think about where that improvement came from. I was training, sleeping and eating well during the experiment.

In addition, I was highly motivated and felt good. My improvement could potentially have just been down to a well structured, good quality block of focused training.

There is potential for a placebo effect too. Placebos can be a powerful thing and are currently at the cutting edge of science. Peer-reviewed studies repeatedly show that if you believe something is going to make you better/faster, it often will. I may have benefitted from a placebo effect.

Thanks to Dr Mark Cole and the University of Nottingham School of Life Sciences for their help in this feature. For more information on renting or buying altitude systems, head over to the Altitude Centre.

Five breakfasts for cyclists

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Oliver Bridgewood - no, Doctor Oliver Bridgewood - is a PhD Chemist who discovered a love of cycling. He enjoys racing time trials, hill climbs, road races and criteriums. During his time at Cycling Weekly, he worked predominantly within the tech team, also utilising his science background to produce insightful fitness articles, before moving to an entirely video-focused role heading up the Cycling Weekly YouTube channel, where his feature-length documentary 'Project 49' was his crowning glory.

-

Man hands himself in to Belgian police after throwing full water bottle at Mathieu van der Poel during Paris-Roubaix

Man hands himself in to Belgian police after throwing full water bottle at Mathieu van der Poel during Paris-Roubaix30-year-old was on Templeuve-en-Pévèle cobbled sector when television pictures showed the bottle hitting him in the face

By Tom Thewlis Published

-

'I'll take a top 10, that's alright in the end' - Fred Wright finishes best of British at Paris-Roubaix

'I'll take a top 10, that's alright in the end' - Fred Wright finishes best of British at Paris-RoubaixBahrain-Victorious rider came back from a mechanical on the Arenberg to place ninth

By Adam Becket Published

-

'This is the furthest ride I've actually ever done' - Matthew Brennan lights up Paris-Roubaix at 19 years old

'This is the furthest ride I've actually ever done' - Matthew Brennan lights up Paris-Roubaix at 19 years oldThe day's youngest rider reflects on 'killer' Monument debut

By Tom Davidson Published