Werking cycles custom frame review

A custom bike is the ultimate N+1 – but does the hype around bespoke frames really stack up out on the road?

A springy and responsive frame which ticked the compliance v stiffness boxes expertly for the bike rider it was designed for. No real aero gains to speak of, but a low weight which certainly shone. A bit of geometry indecision still hanging around, and it could well be worth making sure you're settled into your co-ordinates before investing.

-

+

Lightweight

-

+

Perfect balance of compliance and stiffness

-

+

Expert handling

-

-

No visible aero features

You can trust Cycling Weekly.

Bikes are simpler than people - you tend to know if you like them straight away - and I certainly felt favourably towards my Werking custom bike from the very first ride.

There is something undeniably special about a custom frame. A bike that is designed to suit you, and only you - and might well cause someone else to spontaneously combust should they attempt to ride it (or at least, that's what I told them).

The custom bike I've had on test for the last four months was built by Andrea Sega, in his Trentino workshop, nestled in the Dolomites region of Italy. The geometry was designed by Lee Prescott at Velo Atelier, based in Warwickshire.

The fit took place in July 2017, and the bike itself arrived in April 2018. However, as a one-man band it's understandable that Sega would have prioritised paying customers over review bikes in the production queue – you wouldn't expect the process to take that long in normal circumstances.

I've been knocking out everything from crit races to road races and 100-mile holiday rides on this black beauty (setting the tone early: I like it), so she's now covered thousands of kilometres in a range of environments

The fit process and resulting geometry

A custom bike is only as good as the fitter who devised the geometry.

Prescott's career accolades range from being lead designer at Pashley bikes to creating the Hidden Nation BMX brand, and working as a consultant in ergonomics for supermarkets making checkouts that won't result in repetitive strain injury for employees.

Now, he owns the Velo Atelier bike fit facility in Warwickshire, as well as creating his own Meteor Works custom Steel bikes.

Prescott measured me up – from my head to my toes.

One of the things I was keen to look at was the need, or lack thereof, of 'women's specific bikes', historically designed to cater for women's shorter bodies and longer legs, as a percentage of their height. The below data compares limb lengths, as per the Dreyfuss Human Scale for 'average' men, women, and myself:

| Row 0 - Cell 0 | % of height me | % of height women | % of height men |

| Upper arm | 17% | 16% | 16% |

| Lower arm | 14% | 14% | 15% |

| Upper leg | 25% | 24% | 24% |

| Lower leg | 23% | 23% | 24% |

Of course, the beauty of a custom bike is that there's no need to cater for the 'average' since everything becomes about the individual. But it's interesting still to note that there's no statistically relevant differences between 'average' men, women, or myself (cue: jumping from the rooftops shouting "I'M NORMAL").

The fit, completed on my own bike, took into account my flexibility and core strength plus consultation with physiotherapists at the adjacent Core Clinics unit, which caters for pro athletes as well as amateurs.

As someone who is a tad hypermobile, I've since been on a journey of core strengthening which has indeed helped to stabilise my overly bendy back. There's still a long way to go (bike riding, as in life, is a progression), but this focus has undeniably resulted in fewer injuries over the 2018 race season.

Finally, I discussed my riding plans and preferences with Prescott. I wanted a bike which I could race on the road and in crits, so it needed to be light and stiff. I shared with him my personal favourite bikes: Specialized Tarmac/Amira, the Ridley Noah/Jane and the Canyon Ultimate.

My weight was also taken into account, as this will determine the carbon layup formulated to balance out stiffness with compliance and any necessary extra grams.

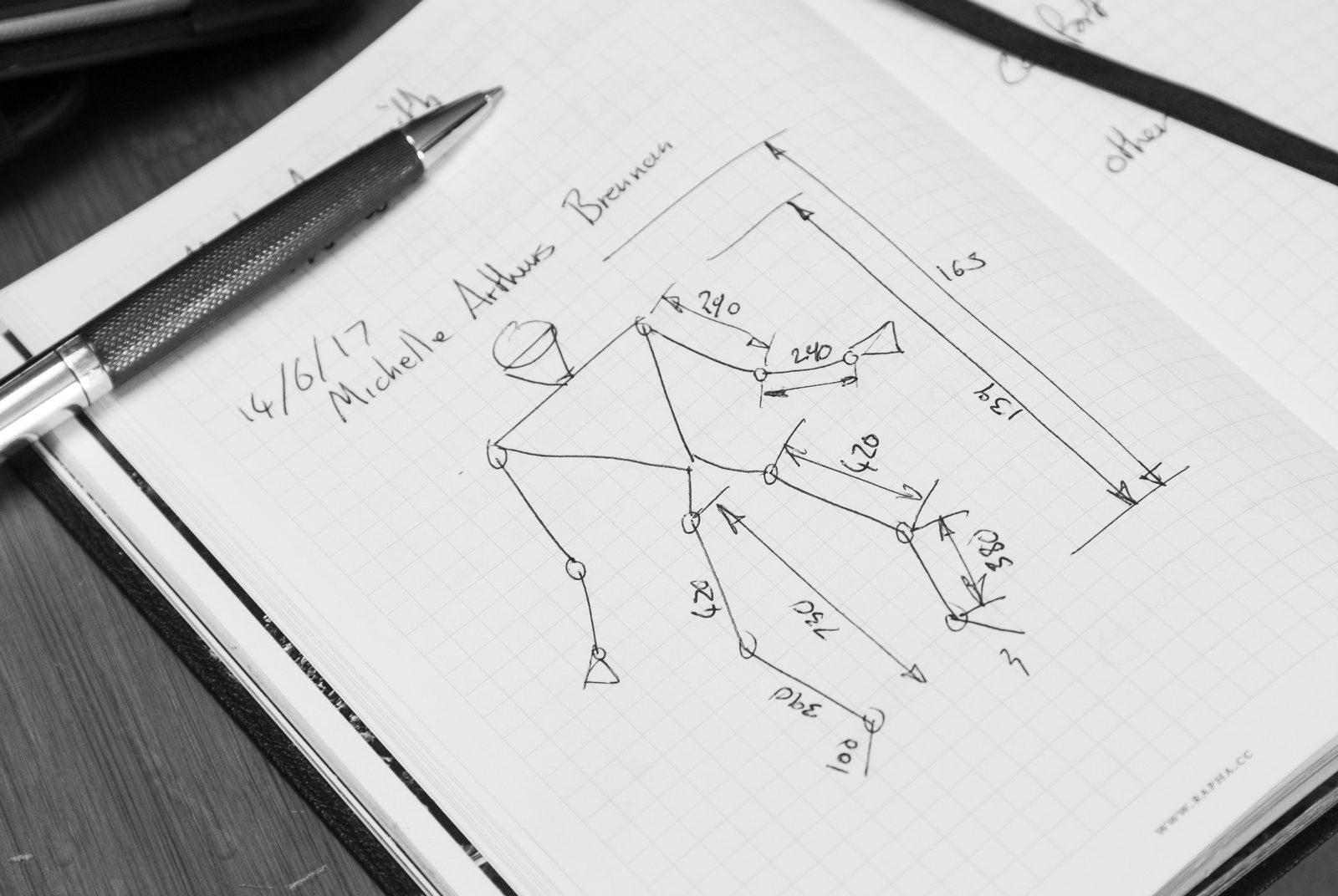

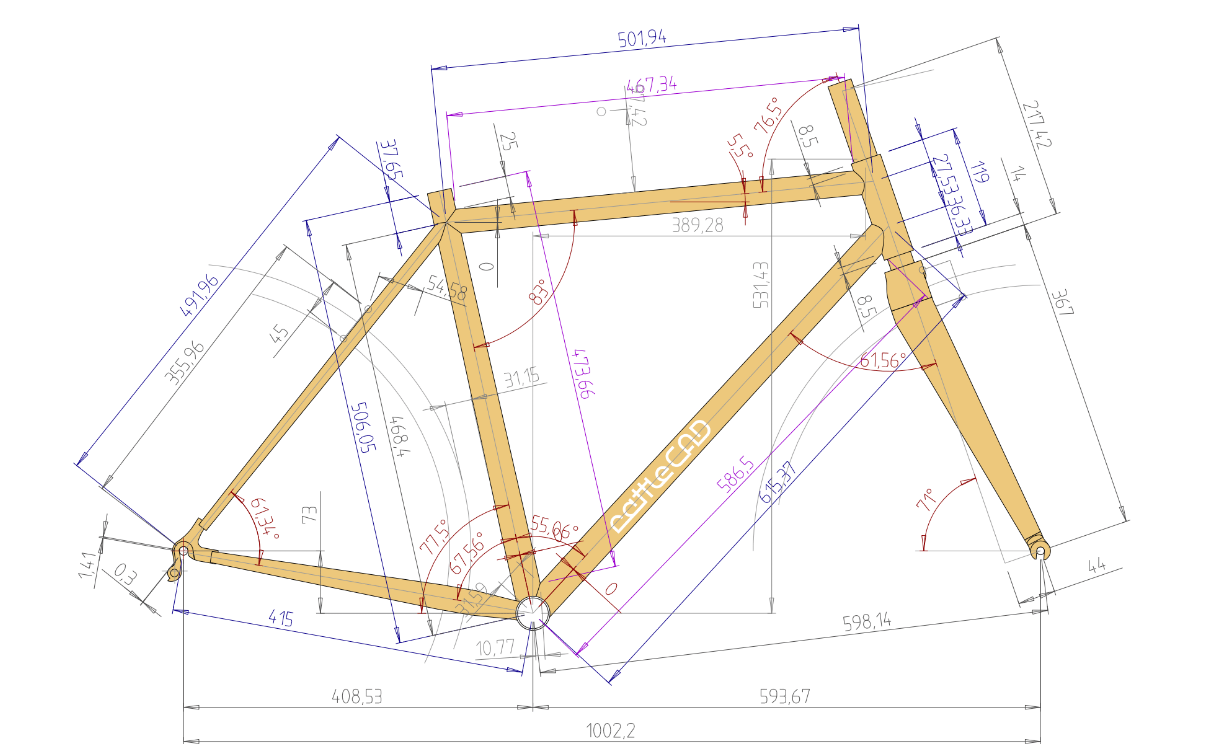

The resulting geometry chart, in a huge amount of detail, looks thus:

When we want to make geometry digestible, we use stack and reach.

The key numbers, then, are 379 (reach) and 537 (stack). The reach comes out pretty comparable to a Tarmac or an Ultimate, whilst the stack is a little higher - but bear in mind that the bike comes slammed and cut, without the option of using any spacers.

| Row 0 - Cell 0 | Stack | Reach |

| Werking CC | 537 | 379 |

| Specialized Tarmac 52 | 527 | 380 |

| Canyon Ultimate XS | 522 | 378 |

Prescott is something of a bike aesthetics traditionalist, and specced the bike with a 90mm stem, explaining that the 'long stem fashion' is something that emerged from a time when bike geometries simply weren't aggressive enough for the pros, meaning they had no choice but to size down and add long, negative angle stems.

Good handling, he says, is obliterated by this trend, hence he uses a formula based on a percentage of top tube length - and he reckons that makes my sweet spot 9cm long.

The 71º head angle and 102cm wheelbase pitch the build a little closer to a Canyon Ultimate than a Tarmac, being a touch less aggressive and promoting stability.

The bars - at 36cm - are narrower than I've ever used before, too, typically I'd opt for 38cm.

Frame construction

The bike - Werking's 'Anormale' frame - was built up by Andrea Sega in his Dolomiti workshop.

Custom steel bikes are generally more common than custom carbon - because the former doesn't usually use a mould, whereas carbon frames typically do.

Evidently, it is possible to make a custom carbon bike - in this case, the tubes (either bought in externally or made by Sega himself to suit the rider's weight and power requirements) are cut and mitred, exactly as per a metal tube would be, then fixed in a jig and glued using epoxy resin. Each joint is then wrapped with specifically shaped pieces of prepreg carbon.

The tubes themselves are selected based on rider weight and the layup required to create the right mix of strength and compliance. These can't be totally custom, but as an example, Dedacciai top tubes come in thirty different layups - so there's enough options out there to get it pretty personal.

Of course, all bikes need to be strength tested - in the case of mass produced frames, one or more of each frame or component is put through vigorous testing, which is something that always looks pretty cool on a factory tour.

This isn't possible with custom frames, so instead an 'average' frame is subjected to the ordeal. Since the custom frame has more joins - which should be areas of the frame that are stronger - Prescott assures me that a custom frame should be tougher than an off-the-peg model.

Not only that, there's no excess carbon, gloopy resin residue or other monstrosities which can befall mass produced models.

"If you were to cut a moulded bike in half, the internals of it are not pretty. The tubes that Andrea is using, if you cut them in half, they’re perfectly smooth and clean which means that you don’t get all those little stress rises," Prescott says.

"The main benefit is that it’s totally customisable, you’re not having to work within the confides of a mould. Moulds are great for mass production, but you are stuck with the geometry that that mould was designed for," he adds.

Finishing kit

Admittedly, we didn't cheap out.

If you're going to have a custom bike, built in Italy, Campagnolo is the only choice and I opted for Super Record (£2,399). I plumped for a semi-compact (52/36) with a fairly wide cassette (11-29) - that's because I live in a valley so the only way out includes quite a few slopes.

The bike was shod with Black Inc Black Thirty wheels (£1,800) to offer the best compromise between road racing hoops for hilly courses and flat out crit sprints. These were fitted with Pirelli PZero Velo tyres in 25c (£100). The finishing kit was all Black Inc, too (£910).

The full build cost was, then, was £8,709 and the weight - with saddle and pedals - is 6.8kg.

This is far from cheap - but it's worth bearing in mind that the frame itself, including the fit, was £3,500 which is easily comparable to top end off-the-shelf jobs.

The paint job looks nothing like what CW's in-house designer specced. I'm told there was an issue with the painter, and in the end it was decided that it would be better to make the bike happen than to wait.

Of course, where I a paying customer I'd not expect that to happen. In hind-sight, I rather like the stealthy black though the red flashes look very much inspired by the blue streaks on Pinarello's Team Sky bikes.

I also have to admit that I'm not a big fan of the logo font - and maybe that's something for Werking to, erm, work on.

The ride

I'd be lying if I said it wasn't love at first ride.

My first outing consisted of about five laps of the CW car park, and though it's far from a thorough test I always find that first impressions rarely alter much.

My immediate impression was of an extremely responsive ride with handling that was perfectly situated on the marker between being planted and secure and twitchy and fast.

Around a week later, I took the bike with me for a week in Girona. There, nothing changed - on long descents I felt superbly in control.

In hilly events through the 2018 race season, the weight drop of this from my previous race bike has been absolutely revolutionary.

I've always maintained thought that much of a result really comes down to the rider as opposed to the machine, and I still hold by that - but climbs have felt significantly easier on this steed and I do think it's helped me out on some of the more gravitationally challenging courses.

Notably, where off-the-peg manufacturers share wind cheating data around their frames, there's none of that from Werking. A swift glance at the tubes tells you this isn't a machine which prioritises aerodynamics.

Personally, this doesn't bother me - I think it's stronger legs that'll help me in a sprint or a breakaway more than a correctly positioned Kammtail Virtual Foil - but someone who places a heavy emphasis on time trials or wants to maximise every watt they've got may disagree.

The reach - including the length of the Campagnolo hood, which is greater than my previously used Shimano preference - measured about 2cm longer than on my most used race bike, and the drop was greater too by a few centimetres.

Initially, I found the extra reach and drop a little off-putting on long climbs, as though I was over-reaching. However, after a couple of weeks of riding I was merrily accustomed.

As is perhaps helpful in a bike reviewer, I'm a little bit chameleon-like in terms of the reach and drop I like in a bike. Which meant a couple of months down the line, after a few rides on a more aggressive machine, the reach of the Werking suddenly felt too short.

Prescott's assessment of my ideal position is most probably as it should be - indeed at least two other bike fitters have put me at near identical co-ordinates, so I'd not dispute it.

However, it doesn't mean I'm not occasionally tempted to give myself some extra length with a new stem. With any 'normal' bike that'd be par for the course, but somehow when it's custom - and the fork angles have been so carefully tailored to work in tandem with the set up - doing so seems somehow sacrilegious.

There are two common reasons for embarking upon a custom journey: you can't get comfortable on what the industry has to offer, or that you want an N+1 to rule them all - the ultimate bike that fits you like the missing lid to that bidon which you found at the back of the cupboard last year.

I don't really fall into the first camp. With regard to the second category, since bodies adjust over time, I'm not completely convinced there is such a thing. I for one know that I'm liable to alter my reach and drop as the mood dictates.

All this said, bear in mind that a custom bike, like any other, is adjustable with component swaps - and it's highly unlikely you'll ever want to make such big changes that this won't be possible.

The most notable element of the Werking still stands, regardless of my fit indecision: the carbon itself feels like the best layup I've ridden ever, and the handling is absolutely spot on - in a way that perhaps only a uniquely tailored bike can offer.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Michelle Arthurs-Brennan the Editor of Cycling Weekly website. An NCTJ qualified traditional journalist by trade, Michelle began her career working for local newspapers. She's worked within the cycling industry since 2012, and joined the Cycling Weekly team in 2017, having previously been Editor at Total Women's Cycling. Prior to welcoming her first daughter in 2022, Michelle raced on the road, track, and in time trials, and still rides as much as she can - albeit a fair proportion indoors, for now.

Michelle is on maternity leave from April 2025 until spring 2026.

-

'This is the marriage venue, no?': how one rider ran the whole gamut of hallucinations in a single race

'This is the marriage venue, no?': how one rider ran the whole gamut of hallucinations in a single raceKabir Rachure's first RAAM was a crazy experience in more ways than one, he tells Cycling Weekly's Going Long podcast

By James Shrubsall Published

-

Full Tour of Britain Women route announced, taking place from North Yorkshire to Glasgow

Full Tour of Britain Women route announced, taking place from North Yorkshire to GlasgowBritish Cycling's Women's WorldTour four-stage race will take place in northern England and Scotland

By Tom Thewlis Published

-

Positive signs for UK bike industry as Halfords cycling sales grow

Positive signs for UK bike industry as Halfords cycling sales growRetailer admits that the impact of Donald Trump's tariffs remains to be seen

By Tom Thewlis Published