Looking for your next cycling challenge? Quebrantahuesos is an absolute monster

Looking for your next cycling challenge? Quebrantahuesos is a 205km Gran Fondo in Pyrenees with 3500m of climbing on closed roads. Here is our guide to the event and our own experience riding it

Quebrantahuesos is Spain's largest Gran Fondo and takes place the third Saturday of June in the stunning, but brutal setting of the Pyrenees on completely closed roads.

The name Quebrantahuesos literally translates to "bone breaker" and is also Spanish name for the Bearded Vulture, a endangered bird only found in the local area. It's an ominous and fitting title that leaves you with a good idea of what can be expected.

>>> How to prepare for an overseas cycling event

The event has been going for 26 years and was originally started by the local Peña Ciclista Edelweiss cycling club. Since humble, grass roots beginnings, the event ballooned in Spain's biggest Gran Fondo.

With 11,000 entrants, Quebrantahuesos is huge. Despite the large number of riders, the event remains relatively unknown in the UK, especially compared to events such as La Marmotte and the Etape du Tour - I was one of only 82 competitors from the UK this year. Perhaps Quebrantahuesos is like a cool indie band that none of your friends have heard of yet, but are destined for big things in the UK.

When and where is it?

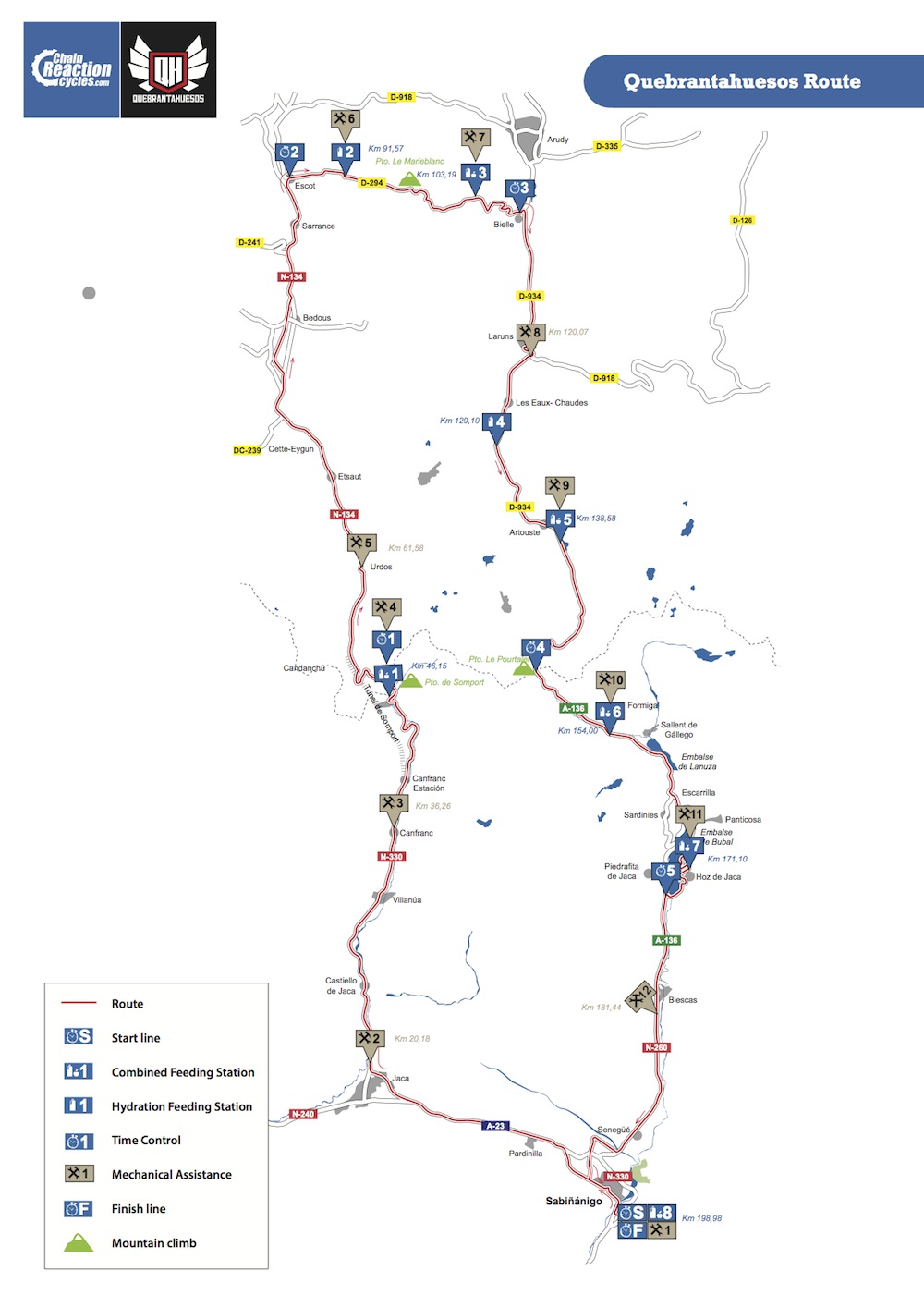

The route starts and finishes in the small town of Sabiñánigo, in northern Spain and the event is held annually on the third week of June. From there you head North into the Pyrenees, taking in the Col de Somport, Marie Blanque and Portalet. All three climbs are Hors Catagorie and the whole route is on closed roads.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

My experience riding the event

One of the biggest challenges riders face in Quebrantahuesos is the heat. Staying hydrated is tough and with temperatures of 30ºC and higher common, the heat can be very challenging for riders coming from more milder climes. However, in 2016 when I rode, instead of the unrelenting Spanish sun, we had to contend with mild temperatures and sustained rainfall, which was unusual for the event.

The average temperature for my ride was just 12ºC and as I lined up at the start at 6:30am it was just 6ºC according to my Garmin. While unusual for Spain, I took comfort in the fact that I had a large amount of experience riding in similar conditions. I struggled to hide my amusement as local riders entered the starting pens, shivering, dressed seemingly for arctic warfare with full deep tights, jackets, gloves and buffs.

You are set off in waves and the organisers do a great job both in terms of the size of waves and gaps between them. The wave you are in depends on your number with the first wave containing ex-pros, celebrities and riders who have previously recorded fast times. Five-time Tour de France winner Miguel Indurain rides the event most years and was riding this year too.

Having dressed for the ride and not to be stood in a chilly starting pen, I was glad to get moving and get warm. I was aiming to do a decent time, so instantly started moving up through my wave, positioning myself near the front of what was a huge peloton.

You head out on a huge highway with motorbike outriders. The bunch was much safer and relaxed than what I have experienced in events such as RideLondon. It struck me that the average rider doing Quebrantehuesos has much more cycling experience and have probably been cycling longer than those tackling a UK sportive.

This is evident, not just in the group riding skills, but also in the level of their kit (lots of riders on tubulars), and their clothing, which is often custom club or team kit.

The pace was high and terrifically exciting. It's not often you get the chance to be swept along in the slip stream of a huge bunch doing 50kph on closed roads. After a few minutes near the front of my peloton, I clocked three riders, all in the same team strip, motor through on the right hand side and straight off the front of the bunch. Not everyone seemed interested, but I instantly figured that these three were going for 'a time.'

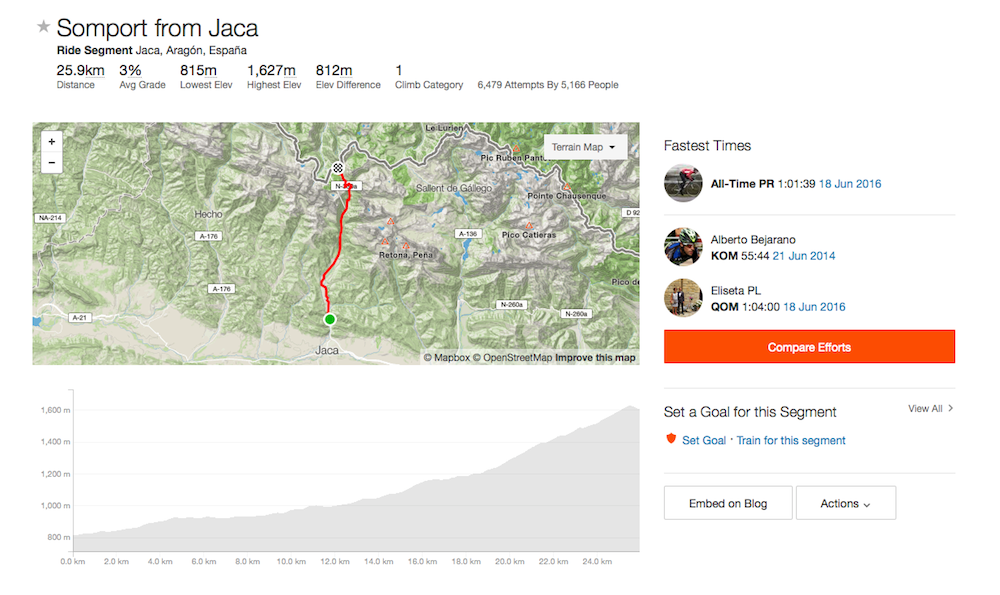

Without hesitation, I sprinted onto the back of them. We were joined by a couple of other riders and set about bridging to the wave in front of us. It was a hard 15-20 minutes of riding in no-man's land, but we caught them just ahead of the first major test of the day - The Col du Somport, which is 26km at 3% gradient with the final 10km averaging 6%.

The Somport is normally a very busy road, making it not suitable for cyclists. I rode the climb pretty hard, as I wanted to try and stay with some of the strong riders around me, the hope being I could get a decent tow off them. With the rain pouring, the support on the climb was fantastic - enthusiastic locals cheering, ringing cowbells and running along side, makes you feel like you are riding the Queen stage of a Grand Tour and certainly spurs you on. As I crested the summit, spectators were even offering news paper to stuff inside jerseys.

The descent off the Somport was very wet. Fortunately I think this actually made it safer, with riders being sensible and not taking risks. It became very clear on this wet descent that the marshalling was the best of any event I have done. Any potentially hazardous section or corner was preceded by large signs and loud and bright marshals, giving you plenty of warning. This makes everything much safer, and crucially, increased my enjoyment.

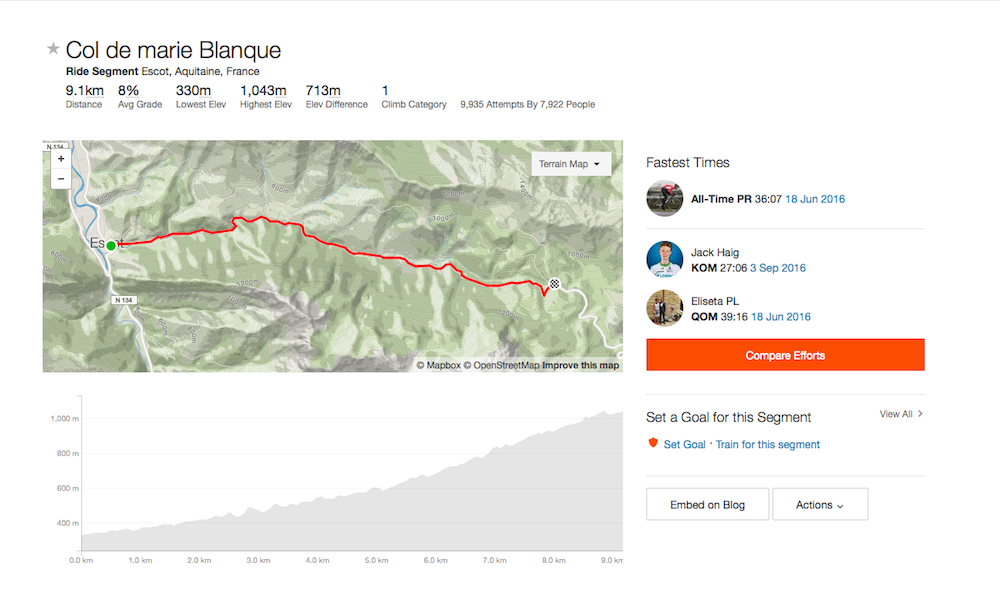

At the bottom of Somport, groups once again formed and allowed us to bomb along at 50kph, heading towards the village of Escot and the ominous Col du Marie Blanque. Marie Blanque has featured in a number of Tours de France and is rated by Eddie Merckx as one of the hardest passes he ever had to climb.

>>> How to climb the Kitzbuheler Horn, the hardest climb you've never heard of (video)

With stats of 9.1 km at 8% the climb doesn't appear to be especially difficult on paper. Statistics can be misleading. This climb is savage as the final 4-5km don't dip below 10% with each kilometre harder than the last. Pacing is therefore key and it is advisable not to get lured in by the relatively gentle lower slopes. One of the kilometres averages 13% with maximum gradients much higher and I saw many riders reduced to walking large parts.

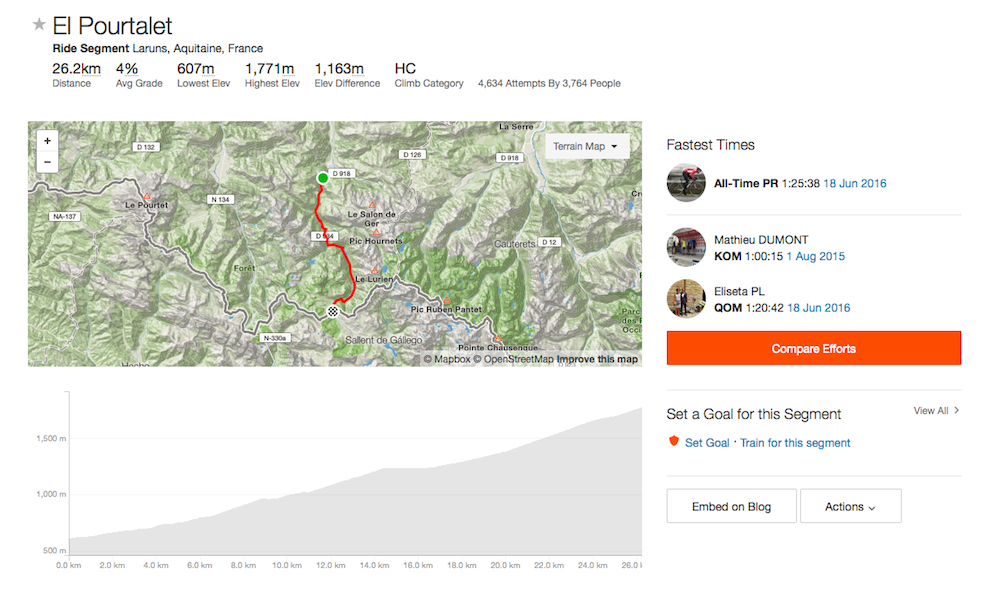

Having successfully negotiated the second of the days climbs and survived the descent, the route took me towards the Col du Portalet. Having ridden pretty hard up the first two climbs, the event started to bite. I unashamedly wheel sucked my way through the valley to the small French town of Laruns.

Laruns marks the base of not just the Col du Portalet, but also the stunning Col d'Aubisque. You wind through the village over a river to a fork in the road where heading right ascends the Portalet and a left turn takes you up the Aubisque. The Portalet is not especially steep, but what it lacks in gradient, it makes up for with its energy sapping length. I was seriously feeling it and the prospect of a 28km col was daunting. My morale took a further hit when my group seemingly accelerated at the base of the climb.

As I watched the companions who had been with me since Somport ride away, I resided myself to lower wattages and slowly (and I mean slowly) ticking off each of the 28km of what is an absolute grind. My group had contained several very small, very lean, very tanned, Spanish mountain goats who I had convinced my self were all ex-pros. They probably weren't, but telling myself they were made me feel better when I was dropped by them.

>>> What to pack for every sportive

My heart rate wasn't high, but fatigue was setting in and my average speed was plummeting like Felix Baumgartner. Up until the Portalet it had been a respectable 34kph.

With 9km to go, you reach the dam and there is a feed station near here too. Fortunately it had stopped raining by this point and I took to the task of just grinding it out and hanging in. It is a beautiful route, even in the inclement weather I experienced. Beyond the reservoir, the last 3-4 kilometres of the climb opens up into a valley and you can see it winding to the summit.

I started to reel in some of my previous ride companions, something which really spurred me on in the final 7% slopes. These riders had tried to keep with the pace of the now out of sight Alberto Contador lookalikes and had spectacularly blown up one by one. On my way to the summit I passed several of them at truly unspectacular speeds.

Video - How to climb the Kitzbuheler Horn, one of the toughest climbs in the world

Sitting in what must have been a rain shadow, the descent off the Portalet was dry. It isn't especially technical and the road is wide enough for four HGVs or coaches. The closed roads really come into their own at moments like this. With wide sweeping turns and tonnes of run off you don't have to brake, it's a hugely enjoyable descent and I was swooping down at 80kph (something I didn't know until I looked back at my Garmin data).

Descending the Portalet, I felt jubilant, I had done it and all that remained was a casual slightly downhill run in to the finish. Except, I hadn't and there wasn't. I, like many others had forgotten Quebrantahuesos' final sting in the tail - the Hoz de Jaca mountain, a short but cruel (10% gradient) climb.

Take a look at the route profile and the Hoz de Jaca looks a like an innocuous pimple next the three monsters you have already conquered, however, it still felt bigger than any climb I have done in the UK and a serious test of both physical and mental strength coming where it does in the event. The descent is pretty technical too, with some sharp bends and the odd bit of gravel. The lower part opens up though and very fast as you head out onto the final run in home.

With 20km to go I was alone as I hit the final run in to Sabiñánigo. With a couple of carrots up the road I decided to empty what was left in the tank and went into time trial mode. I chased down my targets and was myself swept up a short while later by a large group riding through and off. This group was really motoring, so I gladly sat in and gave myself chance to recover. No-one seemed to mind.

The final run in was fun, with loads of support from locals cheering people on. The small town of Sabiñánigo really gets behind the event and there is a really positive atmosphere. Crossing the finish line, I was empty, exhausted and elated with a huge sense of achievement. I collected my medal, pint, large portion of paella and laid down on the grass, well and truly broken. Job done.

My finish time was 6 hours 32 minutes which it turned out, was just a couple of minutes slower than Miguel Indurain. It's fair to say that despite being 52 'Even Bigger Mig' is still in great shape. Also highlighting the slightly humbling notion, that even if all the current Tour de France riders were forced to compete in their fifties, I still wouldn't win!

Tips for the event

- The gate opens at 6:30 so get to start early. You may be waiting around a while but this means you can potentially have ~8000 people behind you. The beauty of this? You will constantly have other riders passing you that you can draft off, increasing your overall speed.

- Take plenty of kit for different weather options. I had planned to ride in summer kit expecting 30ºC temperatures, but fortunately packed Rapha's Wet weather Shadow kit. On the day I had this kit was superb.

- Stay hydrated. I got round with just two 750c bottles (which i finished). However the average temperature was only 12 degrees and about a 3rd of the ride was spent in rain. Having spoken to veterans of the event, you would be advised to stop at feeds and get more fluids in normal conditions.

- Try and save something for the final two climbs

- This event has two routes: Quebrantahuesos Gran Fondo (200 km) and, if you fancy something slightly less daunting, the shorter 'Treparriscos' Medio Fondo (85 km).

The Bike

My bike of choice was a Cannondale SuperSix Evo Hi-Mod in team colours. With several monster climbs, weight was at the forefront of my mind, so I made some modifications. It was fitted with Dura Ace Di2, a super-light Fizik Arione 00 saddle and Fizik 00 40cm handle bars. For power measurement I used Power Tap P1 pedals. Although these pedals are quite heavy, they are easy to transport and fit. They were really useful for pacing my efforts on the long climbs too.

>>> Review of the Cannondale SuperSix Evo Hi-Mod Team Edition

The wheels were Mavic's new Cosmic SL C 40mm carbon clinchers. I was nervous at the prospect of using carbon clinchers on long wet descents, but the new Mavic's are superb. Overall, the bike weight was a UCI illegal 6.4kg. It performed superbly and I struggle to think of another machine I would have wanted for such a challenge. Regarding gearing, I opted for 52/36t with an 11-28t rear. You may want consider a 50/30 chainset, if you are worried about the Col du Marie Blanque.

How to enter

The 2017 edition will be held on the 17th of June and you can enter by heading over to the Quebrantahuesos site. Entry is via a ballot which opens in November. Price for sign up lottery is €4. The results of the ballot are announced in January with successful applicants then able to purchase an entry for €60. If you don't have a cycling licence, you may be required to purchase a Spanish day licence for €10 too. Regardless this event represents excellent value. There are also charity places too.

How to get there

The nearest airport is Zaragoza which is about 130km from Sabiñánigo. Both Madrid and Barcelona are about 450km away. Other potential options are Pamplona and Biaritz, both of which are fairly small airports. When visiting the Pyrenees I have flown to these airports and rented a van to transport both people and bikes.

Where to stay

There are quite a few hotels in Sabiñánigo where you may find accommodation, but demand is high, so I recommend booking far in advance, otherwise you could be a significant distance from the starting point. One option many riders opt for is to camp the night before. There are several sites for this.

Note! Sign up for the 2017 edition is now live. To sign up for the event and to find out more information, click here.

Thank you for reading 20 articles this month* Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read 5 free articles per month without a subscription

Join now for unlimited access

Try first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Oliver Bridgewood - no, Doctor Oliver Bridgewood - is a PhD Chemist who discovered a love of cycling. He enjoys racing time trials, hill climbs, road races and criteriums. During his time at Cycling Weekly, he worked predominantly within the tech team, also utilising his science background to produce insightful fitness articles, before moving to an entirely video-focused role heading up the Cycling Weekly YouTube channel, where his feature-length documentary 'Project 49' was his crowning glory.

-

'I have been ashamed for days' - Man who threw bottle at Mathieu van der Poel at Paris-Roubaix apologises

'I have been ashamed for days' - Man who threw bottle at Mathieu van der Poel at Paris-Roubaix apologisesIn a letter to Belgian newspaper Het Laatste Nieuws, the assailant apologised for his action on Sunday

By Adam Becket

-

Meet Tadej Pogačar's new weapon: Colnago’s lightest frame ever — the all-new V5Rs

Meet Tadej Pogačar's new weapon: Colnago’s lightest frame ever — the all-new V5RsParis-Roubaix was the last hoorah on Colnago’s winnigest bike, the V4RS. Enter the new V5Rs, to be raced from the Amstel Gold Race onward

By Anne-Marije Rook